NZ Insights

Māori employment resilient after COVID lockdowns

Finn Robinson

Economist

ANZ NZ Ltd.

One of the good news stories throughout 2020 was the remarkable resilience of New Zealand’s labour market. And one of the most pleasantly surprising things in that regard is that unlike previous recessions, Māori have seen the smallest increase in unemployment compared to other groups.

In this Insight we dig into the numbers to look at why Māori employment has typically been more vulnerable in previous recessions in New Zealand, and why 2020 was different.

- Māori in New Zealand have had a structurally higher unemployment rate than the population average since the data began in 1986. The reasons for this are obviously far more complex than any simple macroeconomic analysis can capture. But this group also typically see a much larger increase in unemployment during recessions. Why is this? Two factors leap out:

- The Māori population is much younger than the overall population of New Zealand, and younger people tend to have much worse unemployment outcomes than average.

- In addition, Māori have historically been more likely to be employed in industries that are particularly exposed to the economic cycle, such as construction and manufacturing.

- While the overall labour force’s unemployment rate at 4.7% is still higher than it was in 2019, Māori unemployment is already essentially back down to its pre-COVID levels – albeit still high at 8.4% (ANZ seasonal adjustment).

- The impact of COVID and the associated border closure has hit some industries hard, while others have largely managed to shrug it off or even benefit. And it just so happens that industries where Māori are currently more likely to be employed have been the ones that have experienced some of the most robust recoveries.

Introduction

An ongoing feature of New Zealand’s labour market has been the disparity in labour market outcomes that different people experience, whether that be associated with differences in region, sex, age, skill level, or ethnicity.

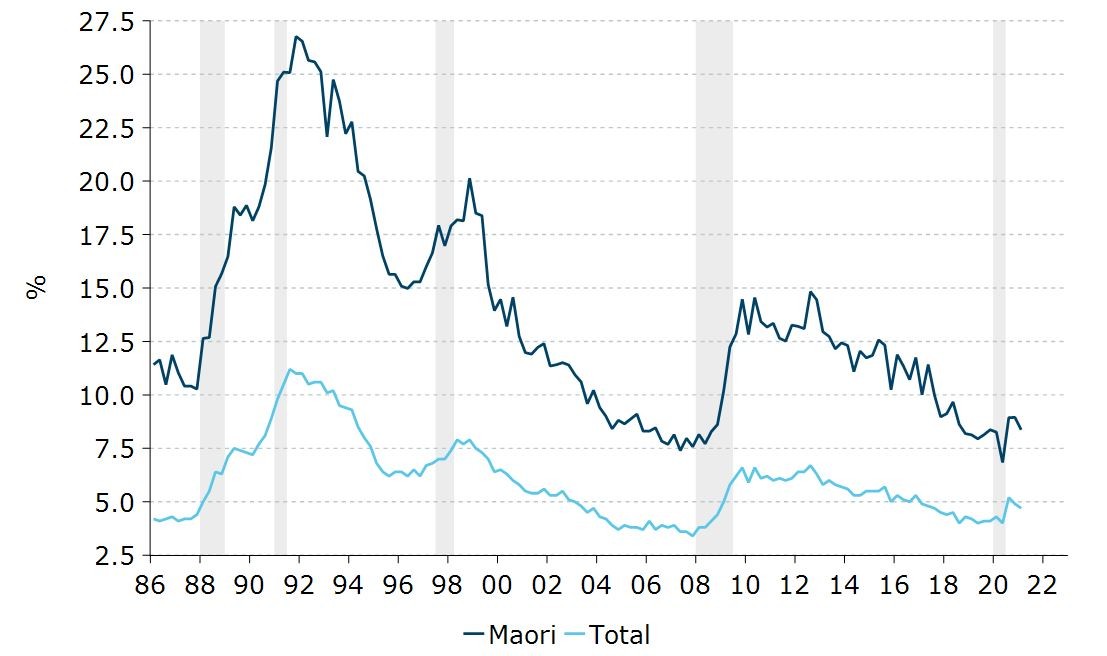

A stark example of this is the unemployment rate for Māori, compared with the population average. From 1986 (the first available data) to the current quarter, Māori unemployment has been higher than the average (figure 1, recessions shaded in grey).

During the 1980s and 90s this difference was particularly large. Unequal labour market outcomes also show up in incomes, with Māori employees earning a median income of $925/week in 2019, versus $1000/week for the country as a whole.

While Māori and national unemployment have broadly trended down since the early 1990s (looking through upticks caused by recessions), the gap in outcomes between has never been erased.

This is a structural feature of the labour market that has persisted through multiple economic cycles.

Figure 1. Unemployment rates

Source: Stats NZ, Macrobond, ANZ Research

The COVID recession has been unique

These differences in labour market outcomes are persistent, and have lasted across multiple economic cycles. But what we can also see is that during individual economic cycles, different people have had very different experiences.

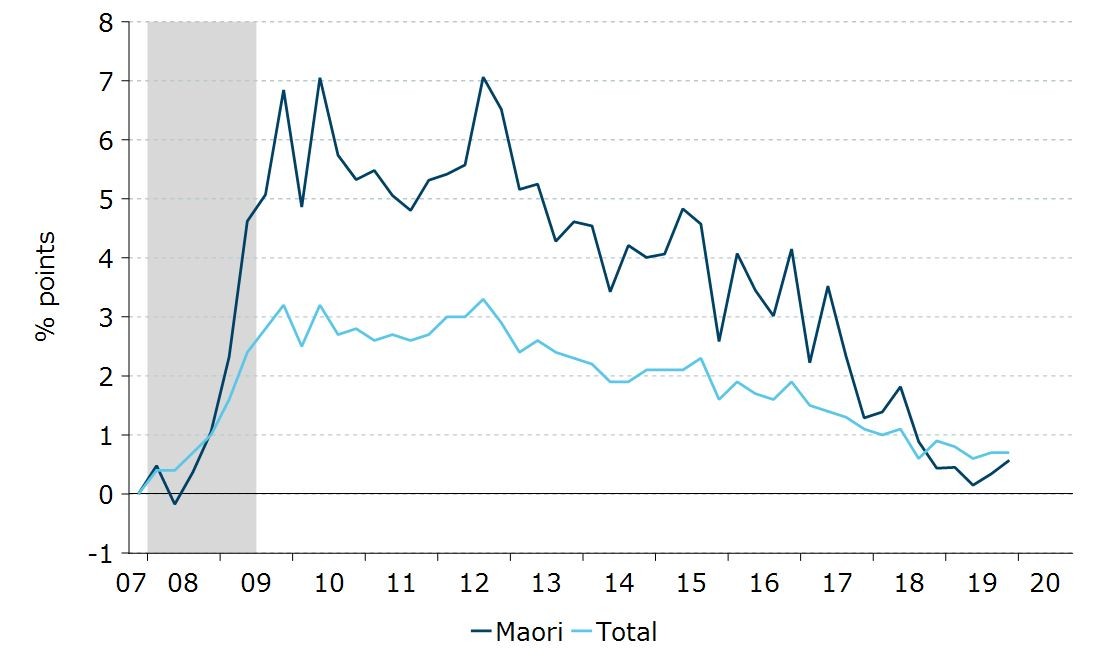

The gap tends to widen abruptly in recessions, and then narrow in the good times. The chart below shows the impact of the global financial crisis (GFC) on unemployment in New Zealand, tracing out the change in different unemployment rates from the onset of the GFC to the end of 2019 (the eve of the COVID-19 recession).

Everyone got hit hard by the GFC, that’s for sure. Unemployment increased over several years.

It only really started falling after 2012, and never actually returned to pre-GFC lows. But what we can also see is that the magnitude of the impact varied immensely. At a headline level, the unemployment rate increased by around 3 percentage points. But for Māori it increased by 7 percentage points.

Figure 2. Change in unemployment rates during and after the GFC

Source: Stats NZ, Macrobond, ANZ Research

The GFC had large, persistent, and uneven impacts on unemployment outcomes in New Zealand, and we never fully recovered from it.

In contrast, it’s become clear that the COVID-induced recession has been nothing like previous downturns. New Zealand has experienced a V-shaped recession.

That is, we went into a very short, sharp economic contraction, and have experienced an equally sharp (hopefully not short!) recovery. And this has resulted in some very different labour market dynamics compared with previous cycles.

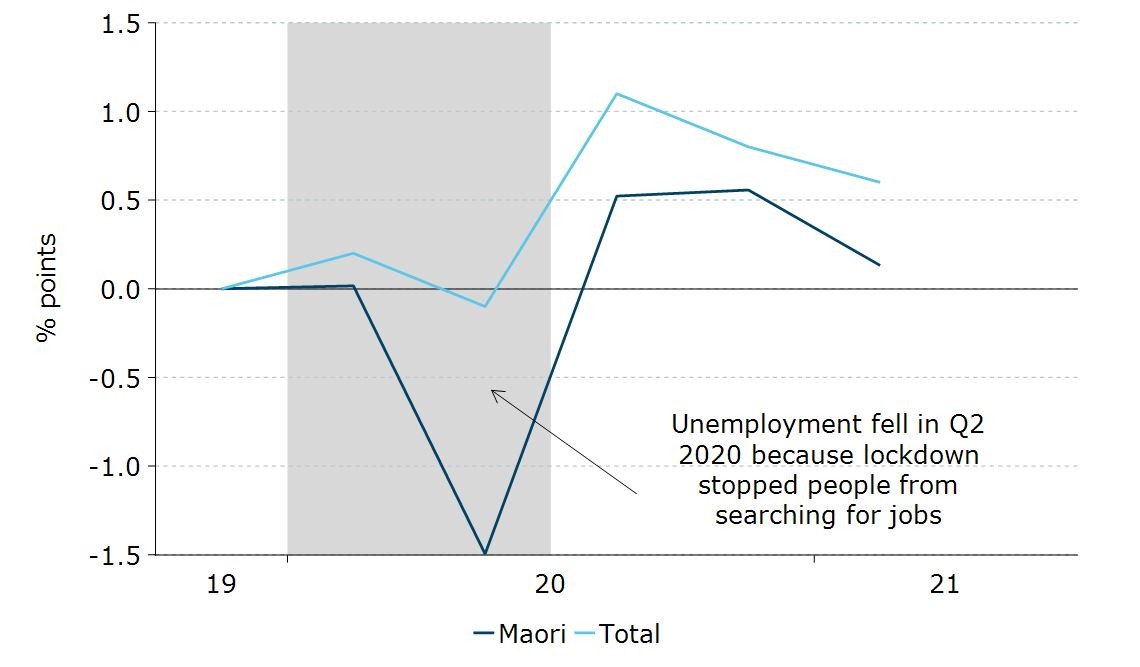

Figure 3 shows the change in unemployment rates since late 2019. Unemployment has increased, but by nowhere near as much as during the GFC. The headline unemployment rate was 1.1 percentage points higher in Q3 2020.

And in contrast to historical experience, Māori have actually seen the smallest increase in unemployment – in fact, Māori unemployment is pretty much back to pre-COVID levels, while total unemployment is still elevated. That’s a sharp reversal of previous trends.

So what’s going on here? Why is Māori employment so much more exposed to ‘normal’ recessions (if there is such a thing), and why has the COVID recession been so much less damaging?

Figure 3. Change in unemployment rates during and after the COVID recession

Source: Stats NZ, Macrobond, ANZ Research

‘Normal’ recessions

Two economic factors can partly explain why Māori employment is generally more exposed to economic fluctuations than average: the age structure of the Māori population, and the industries in which Māori tend to be employed.

We don’t delve into the question of why these factors are as they are, but just take them as given.

Starting with age, younger people tend to experience worse labour market outcomes than average, particularly during recessions. Young people are, to be blunt, more expendable, since they haven’t had time to build up hard-to-find specialist skills and knowledge.

They’re therefore less risky to fire, all else equal – but less risky to hire, too, when things improve, being cheaper.

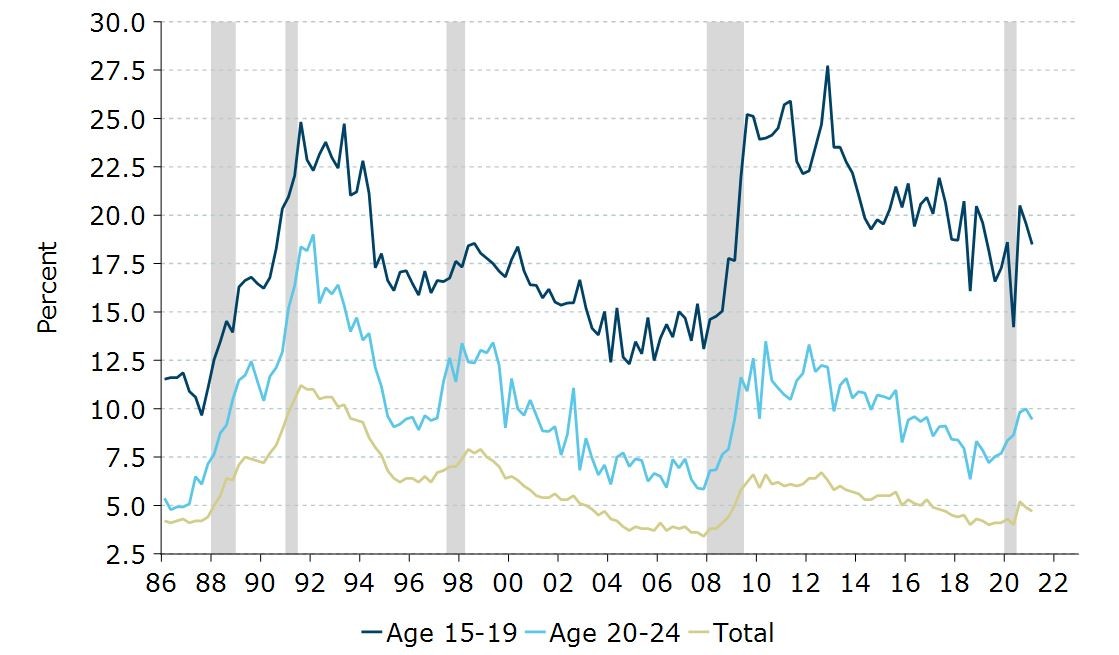

Figure 4 shows unemployment rates for people aged 15-19 and aged 20-24, alongside the headline unemployment rate.

Similar to what we see for Māori, youth unemployment has been structurally higher than average unemployment over the entire sample. Young people also see much larger increases in unemployment rates when recessions hit.

During COVID, for example, the unemployment rate for people aged 20-24 increased around 2.5 percentage points, whereas for the total population it was just over 1 percentage point higher. It also drops more quickly, too – it’s a lot more cyclical and volatile overall.

Figure 4. Youth unemployment rates

Source: Stats NZ, Macrobond, ANZ Research

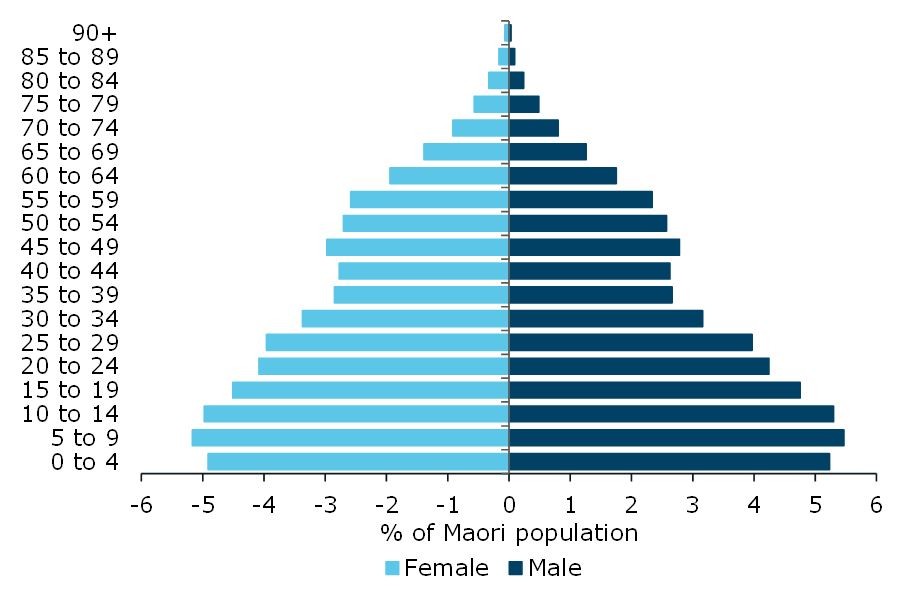

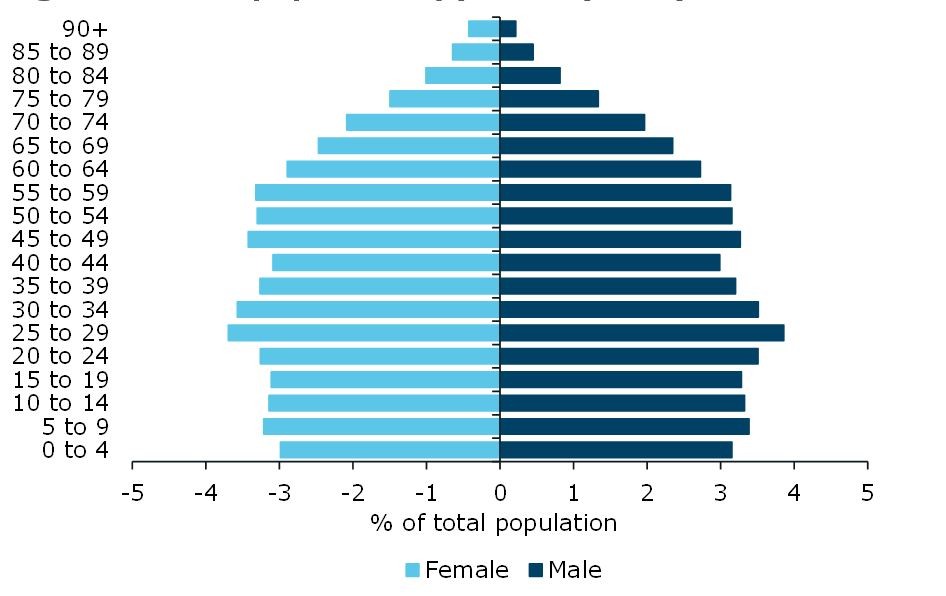

When we look at the age structure of the Māori population versus New Zealand as a whole, we can see that the population is more concentrated in younger age brackets (figures 5 and 6).

That is, the Māori population is much younger, on average, than the total population.

Given that younger people tend to experience worse and more volatile labour market outcomes, it’s reasonable to think that at least part of the explanation for higher Māori unemployment (both in general and during recessions) is due to the relatively young population.

Figure 5. Māori population pyramid (2019)

Source: Stats NZ, ANZ Research

Figure 6. Total population pyramid (2019)

Source: Stats NZ, ANZ Research

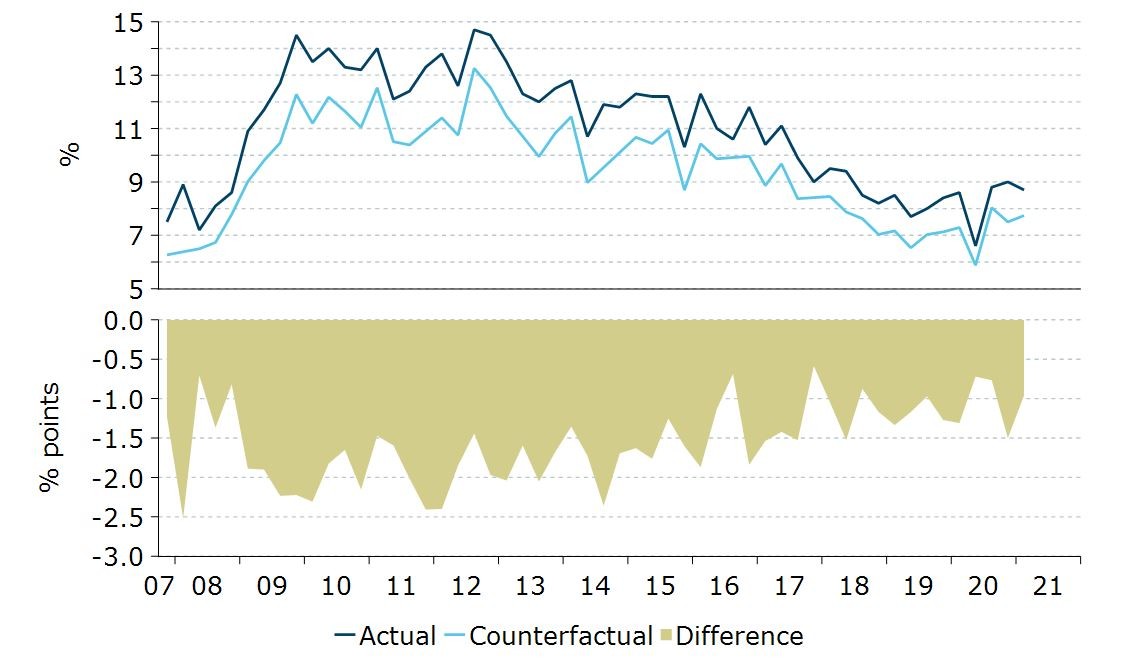

We use a back-of-the-envelope calculation to work out roughly how much lower Māori unemployment would theoretically have been over the past decade, had they had the same age demographics as the total population.

Essentially, we take Māori unemployment by different age cohorts, but use total population shares to sum them together to the get a total unemployment rate.

The result in figure 7 shows that Māori unemployment could have been around 1-2 percentage points lower if the population had the same structure as the total NZ population.

And that difference was largest just after the GFC – which makes sense, since younger people tend to be more exposed to recessions. That doesn’t explain all (or even most) of the worse unemployment outcomes for Māori, but it’s clearly an important variable.

Figure 7. Māori unemployment with different age structures

Source: Stats NZ, Macrobond, ANZ Research

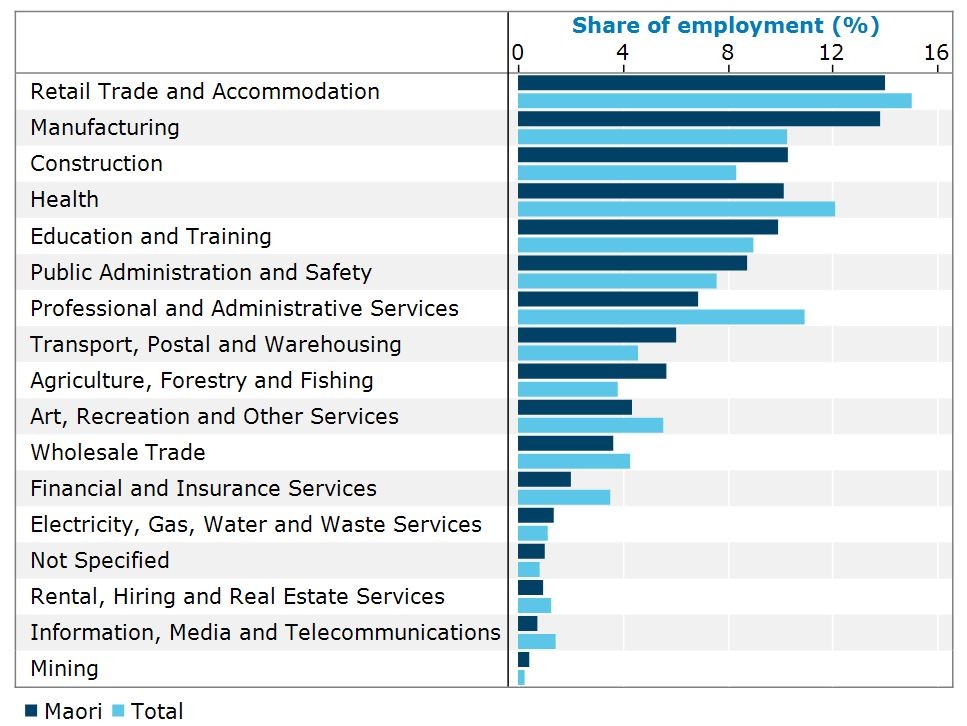

Another factor that could explain why Māori employment has typically been more exposed to recessions is its industry composition. In 2020, the top five industries Māori were employed in were (as a share of the total number of Māori employees):

1. retail trade and accommodation (14.0%);

2. manufacturing (13.8%);

3. construction (10.3%);

4. health (10.2%); and

5. education and training (9.9%).

These were also the top five industries in 2009, although the ordering was slightly different.

Comparing this industry composition with the total population, we can see that Māori employment is tilted a bit more towards manufacturing, construction, and primary industries, while total employment is a bit more heavily weighted towards services, particularly professional and administrative services (figure 8).

Figure 8. Composition of employment in 2020

Source: Stats NZ, Macrobond, ANZ Research

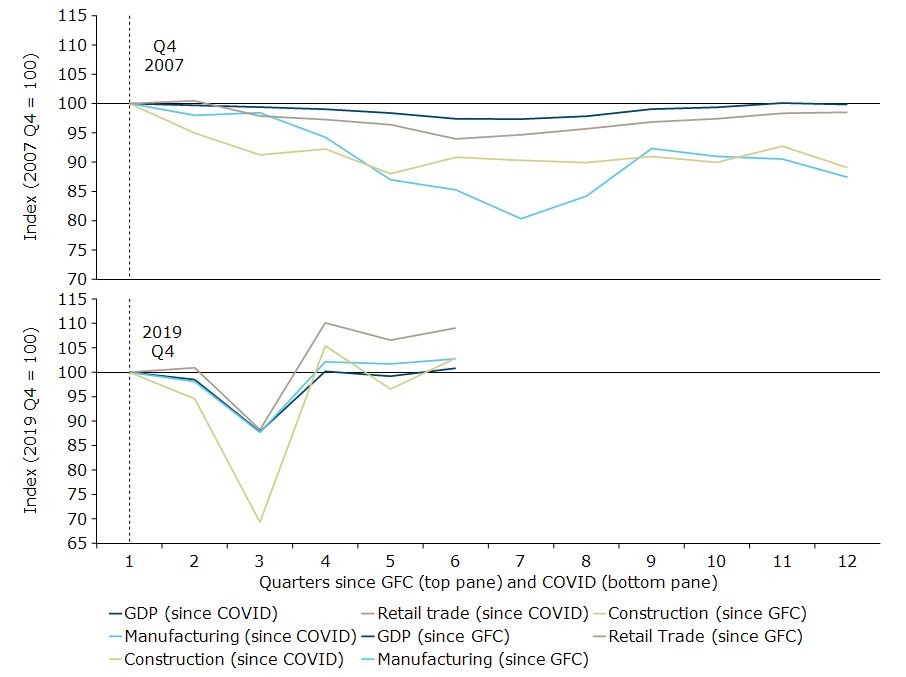

The top three industries – retail trade and accommodation, manufacturing, and construction – have tended to see quite large contractions in GDP during previous recessions.

During the GFC, for example, all three of these industries experienced substantial declines in output, with manufacturing reaching a low of just 80% of its pre-GFC level in mid-2009 (figure 9, top panel).

While aggregate GDP and retail sales had recovered to pre-GFC levels by the end of 2011, the same could not be said for construction until 2014, and for manufacturing until 2017!

Figure 9. GDP during the GFC and COVID

Source: Stats NZ, Macrobond, ANZ Research

In the right place at the right time

But the COVID recession proved very different. While these industries (and total GDP) all took a massive hit in mid-2020, they have already bounced straight back up to above pre-COVID levels (figure 9, bottom panel).

This likely reflects the sector-specific nature of the COVID-19 shock (as well as the rapid fiscal and monetary policy response).

Services industries, particularly those that rely heavily on international tourism, have borne the brunt of the impact of the border closure, while others, once fiscal policy filled the initial lockdown hole, have picked up where they left off, only with lower interest rates.

Some sectors have had an outright tailwind. There was a big substitution towards purchasing goods – particularly durables – during COVID (as opposed to splashing out on overseas holidays).

That provided a big boost to goods-producing industries. And record-low mortgage rates and the suspension of LVR restrictions saw the housing market go gangbusters, with a surge in building consents indicating a strong pipeline of construction work that still needs to be cleared.

So overall the biggest three industries for Māori employment have actually weathered the COVID storm much better than in previous cycles – and this goes a long way to explaining why Māori have experienced a comparatively small and temporary rise in unemployment.

So putting all the pieces together, it looks like a key part of the puzzle for explaining the resilience of Māori labour market outcomes during COVID has been the industry composition of employment.

While construction, manufacturing, and retail trade and accommodation have typically been quite severely impacted by recessions, the sector-specific nature of COVID meant that these industries were to some extent sheltered from the ravages of recession.

The robustness of Māori employment outcomes (and indeed the labour market as a whole) during COVID is genuine good news. But unfortunately, Māori unemployment is still structurally much higher than average, and there is nothing in these results to suggest that the next recession won’t revert back to the cyclical patterns of the past.

Although the RBNZ does monitor Māori and Pasifika unemployment when thinking about the overall performance of the labour market, they can’t resolve structural issues with cyclical stimulus. These inequities are deeply ingrained in New Zealand’s labour market, and require targeted policy responses to address.

RELATED ARTICLES

NZ Business

Māori playing increasing role in Kiwifruit industry

NZ Insights