NZ Business

Locked Out - Covid crisis no game changer for housing affordability

Liz Kendall

Senior Economist

ANZ New Zealand Ltd

The long-term benefits of home ownership are significant, but buying a new home is expensive. Housing affordability has worsened in recent decades; it now costs more to purchase a house and longer to save for a deposit, putting home ownership further out of reach for many.

This is true across most New Zealand regions. Recently, lower mortgage rates have made home ownership costs cheaper, benefiting existing homeowners and those who can enter the market. But those who are locked out of the market cannot reap the same benefits, and rising unemployment and income strains are eventually expected to put pressure on debt-servicing capability of some households.

The RBNZ is providing an important cushion to the economy through lower mortgage rates (and other channels), reducing the blow to both house prices and incomes. But it won’t solve Zealand’s housing affordability problem; that requires a hard look at structural factors.

New Zealand houses are expensive

Houses have become more expensive over the past two decades. House prices have risen dramatically to be 2.5 times higher than in the late 1990s in real terms.

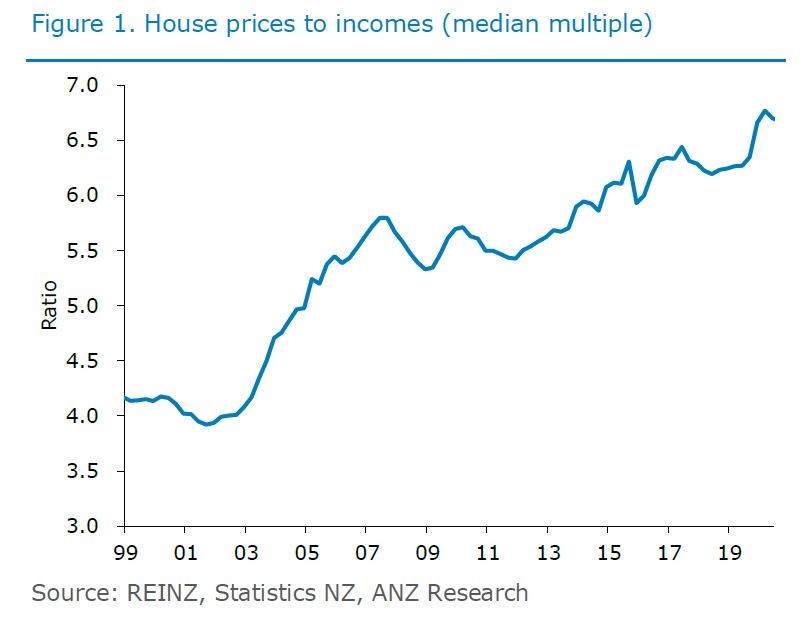

Incomes have risen too, but not to the same extent. House prices have risen from four times to almost seven times incomes over the same period (figure 1).

House prices relative to incomes is not a perfect measure of housing affordability, because it does not take into account the fact that structural declines in mortgage rates have provided an offset by reducing debt-servicing costs.

We consider two alternative measures, which we view as more representative of housing affordability (figure 2):

Note: Based on median house price, median incomes, mortgage and deposit rates, and other costs (rates, maintenance, insurance etc.) assumed to equal 2% of property value.

These measures are illustrative, based on median housing values and incomes. In reality, costs will depend on personal circumstances and the particular house one buys or rents. For example, most purchasers choose a lower-value property as their first step on the property ladder, but the same trends will hold.

Based on these measures, houses are expensive and have become more so. Since the late 1990s, ownership costs have increased from about 35% of household incomes to around 45%, and the time taken to save for a deposit (assuming one is saving 10% of pre-tax income) has extended from 8 to almost 14 years.

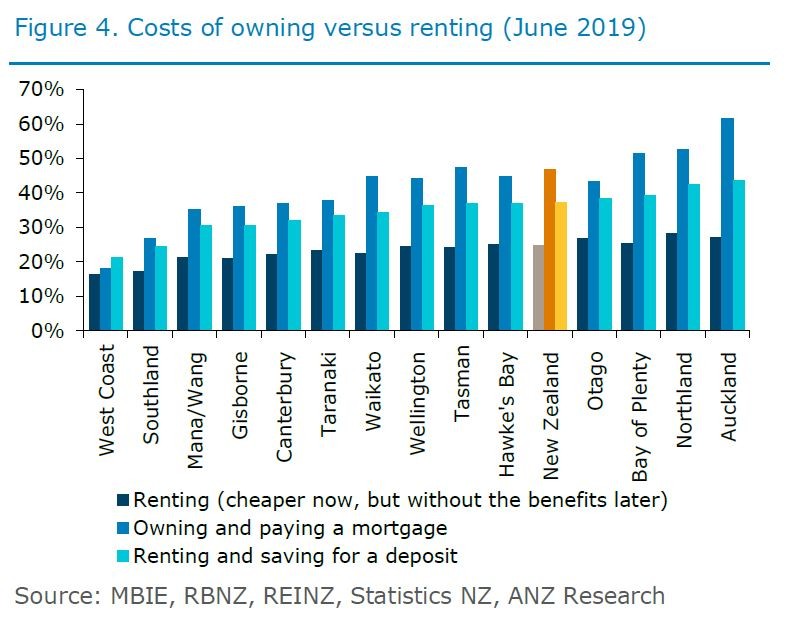

On a like-for-like basis, purchasing a new home costs about twice as much as renting. Weighing up the decision to rent or buy is very situation dependent and is contingent on personal circumstances, costs, preferences, income expectations, taxes, expectations of capital gains, and other perceived benefits.

But for those who do own their own homes, the benefits can be very substantial, including security of tenure and eventual freehold status, especially valuable in retirement. There will always be some who cannot afford to purchase a house to secure these benefits, and the cohort of people who are able and willing to do so has reduced as houses have become more expensive. The rate of home ownership has fallen from 74% in the early 90s to 65% in 2013.

Costs of home ownership can be a significant constraint on housing affordability even with interest rates extremely low. This is because house prices, and by extension debt levels, are very high. Secular declines in mortgage rates have been more than offset by rising house prices over the past few decades.

Most regions are expensive

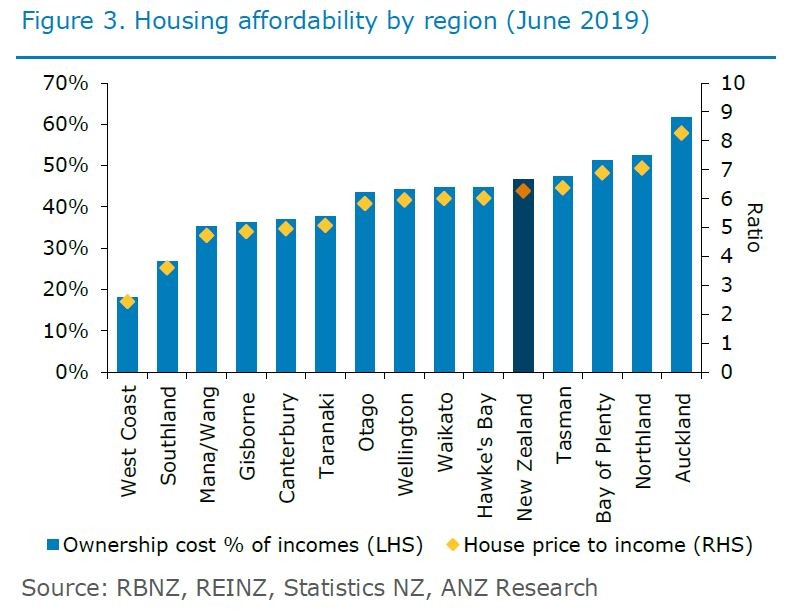

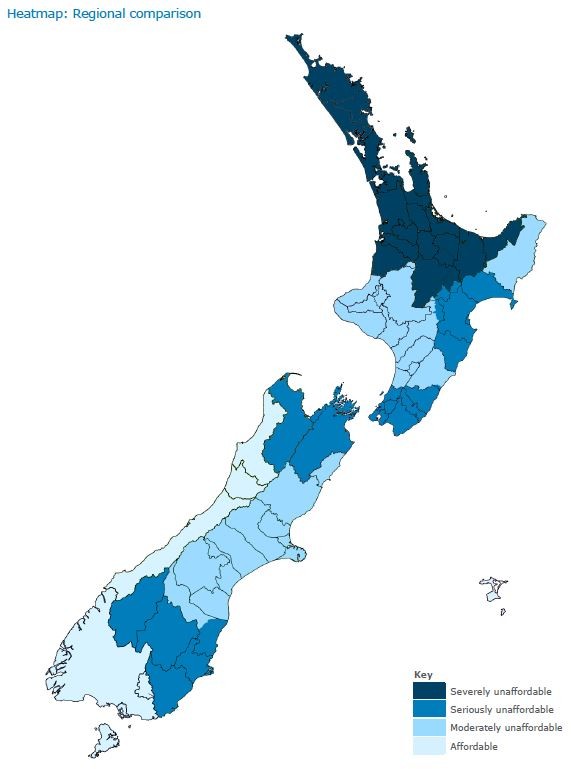

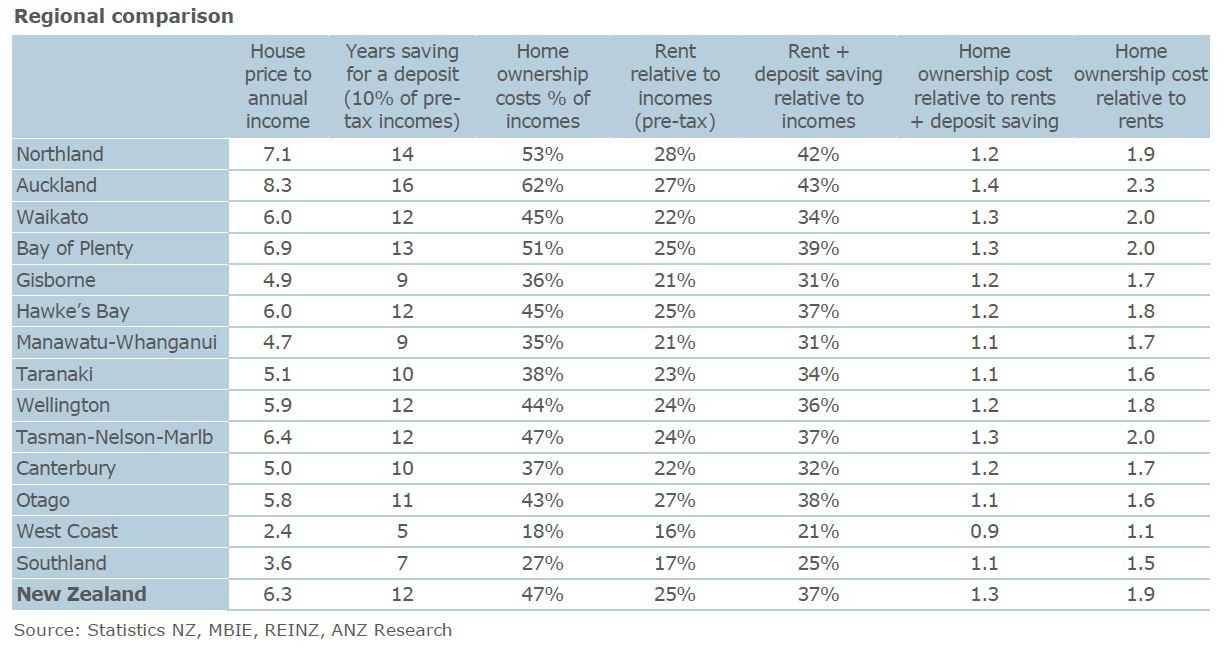

Houses are expensive across most New Zealand regions, with home ownership costs comprising more than 40% of incomes in 8 out of 14 regions, and more than 60% in Auckland (figure 3 and heatmap).

For those looking to get onto the property ladder, saving and renting concurrently on average eats up about 37% of incomes in New Zealand as a whole, and as much as 43% in Auckland (figure 4).

High house prices in regions like Auckland reflect the desirability of living there and also that population growth tends to be strong, with the region getting a significant portion of new migrants.

In general, people (including those with a high willingness to pay) will pay a premium to live in vibrant centres, with amenities, good weather, natural capital, good infrastructure, plentiful jobs, and growth potential.

To some extent, population can adjust to high housing costs, with people gravitating to areas where housing is cheaper, and this does occur to some degree, but it is limited. Generally, people will move to where the jobs are.

When houses in Auckland get more expensive, people may move to Hamilton and Tauranga, but Southland is a less obvious substitute.

High house prices reflect structural factors

The reasons why housing has become more expensive tend to be structural in nature. Demand for housing has been very strong in a supply-constrained environment. Supply constraints exist because of land-use constraints, regulatory restrictions and slow responsiveness of new building.

Demand pressures have been a result of migration-driven population growth, increased credit availability, and a trend decline in neutral interest rates (largely owing to structural factors, not cyclical monetary policy). If housing supply could easily respond, then these demand pressures would result in more building (both more and bigger houses), but in a supply-restricted environment, higher demand ends up being reflected to a greater degree in the price.

Addressing New Zealand’s housing affordability problem would require a hard look at land supply, building regulation, migration settings, and structural policies. Affordability metrics may ebb and flow in the future around current levels as conditions change, but a significant shift is hard to imagine.

With an enormous amount of wealth tied up in housing and changes both logistically and politically difficult, it’s difficult to achieve the sorts of structural changes that would elicit a meaningful difference. The current Government has made efforts to free up land supply and solving greenfields infrastructure funding challenges, but it’s not easy.

Ownership costs a little cheaper recently

Recently, declines in mortgage rates have contributed to resilience in house prices (see full report for more details). For new purchases, the minimum mortgage rate has fallen about 80bps. And we assume this will decline by another 80bps, though the outlook is uncertain. We are currently pencilling in total falls across the curve of 160-195bps between February 2020 and May next year.

The catalyst for further falls is predominantly expected to be a move to a negative OCR next year. No, your bank won’t be paying you to borrow, but it will mean further downward pressure on mortgage rates. QE will also drive the term structure flatter, meaning particular pressure on longer-term rates. However, there is uncertainty about the pass through of these policies to mortgage rates in practice.

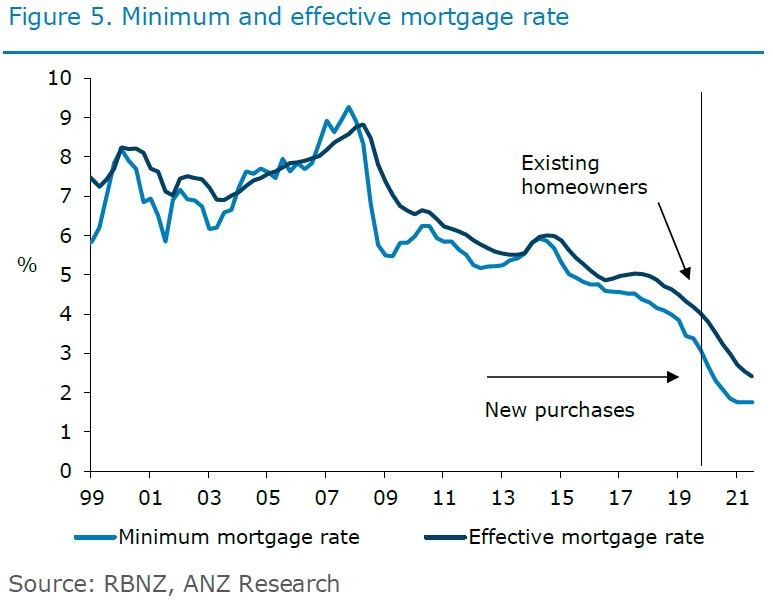

For existing homeowners, the effective mortgage rate on outstanding debt will take a bit longer to decline, as fixed mortgage parcels roll off and are re-fixed at lower rates. We assume that it will fall gradually from 4.1% pre-COVID, to 3.7% now, to 2.4% at the end of 2021 (figure 5).

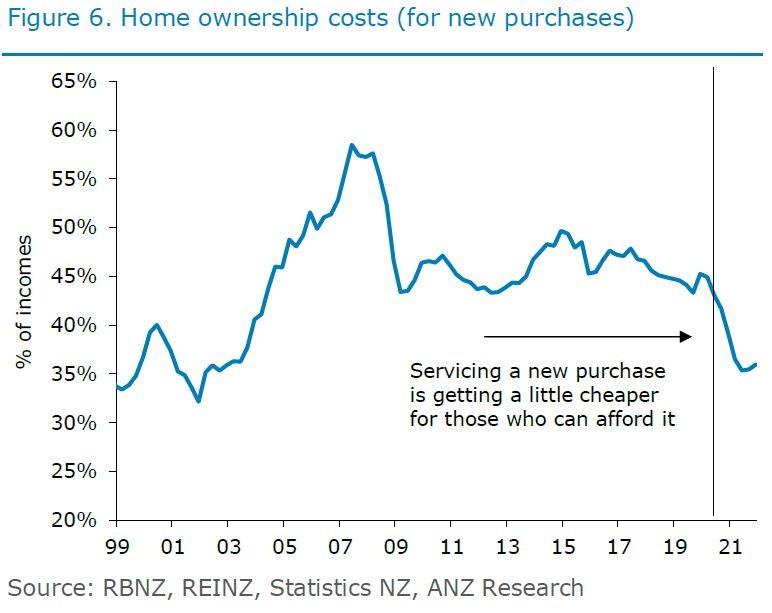

As minimum mortgage rates have fallen, home ownership costs for those entering the market have eased a little to 43% of incomes (figure 6), with incomes also coming under pressure recently.

We expect home ownership costs will decline further, to perhaps 35% of incomes, as mortgage rates fall further, with weakness in house prices dampening costs for new purchases too, but weaker incomes providing an offset.

But income strains to more than offset

Although some new and existing homeowners are benefiting from lower mortgage rates, overall ability to service debt has the potential to be much more negatively impacted by firm difficulties and rising unemployment, especially for those directly affected. This will weigh on house prices and spending generally.

Income strains and job losses are expected to be further exacerbated by the renewed lockdown in Auckland, dampening the GDP outlook, although the extent of this is uncertain. More monetary stimulus and extended fiscal supports are likely to cushion the blow, but the scars of the current crisis are likely to worsen as the lack of normality becomes more prolonged and closed border impacts hit, especially with some businesses coming out of the previous lockdown in an already-fragile position.

The RBNZ is fulfilling a crucial role to cushion the blow, stimulating demand through lower mortgage rates and a range of other channels. But monetary policy is a blunt instrument and can’t offset all of the painful economic adjustment taking place due to the closed border.

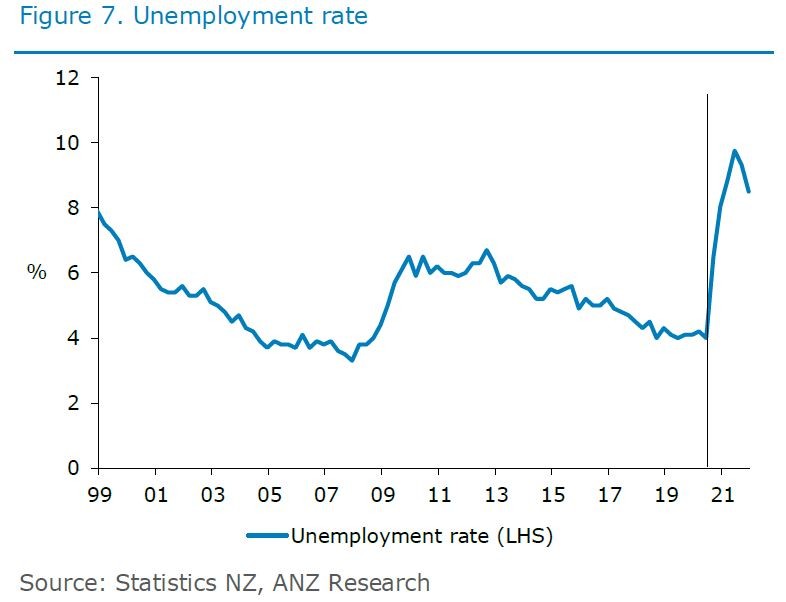

We see unemployment rising to 10% (figure 7), but a bit later than previously expected, with the brunt of the economic impact to become clear later this year.

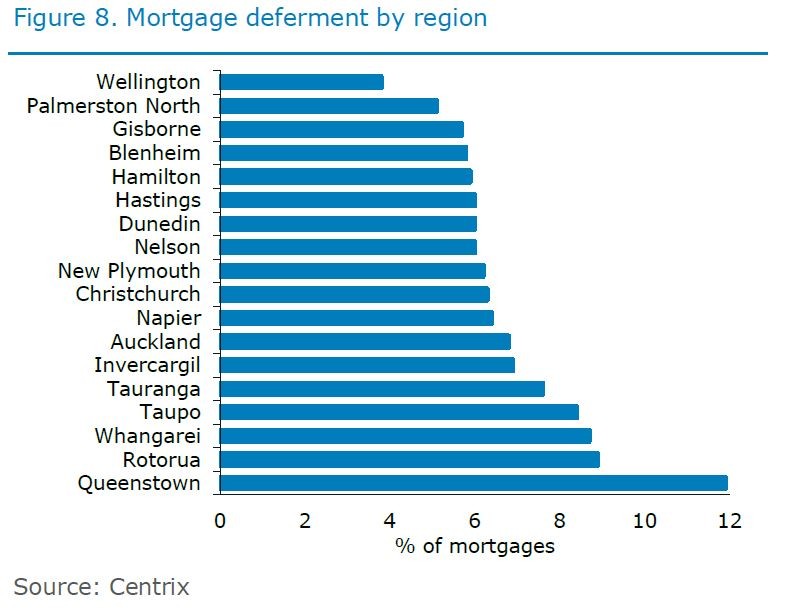

The impact of income strains will be felt unevenly by region. Disparate regional impacts across the country are already being borne out in mortgage deferment data, which suggest that households in tourism hotspots Queenstown and Rotorua are feeling the most financial strain (figure 8).

Some areas are particularly vulnerable to house price falls, while other areas are likely to see more resilient prices.

No game changer for housing affordability

RBNZ stimulus will boost both incomes and house prices, so the implications for overall housing affordability are unclear.

Generally speaking, inflation-targeting monetary policy is a cyclical policy to stabilise the economy, rather than being a structural driver of unaffordable house prices.

There is a risk that the current crisis sees equilibrium interest rates lower for a long time (due to reduced productive capacity in the economy, higher debt burdens and/or lower inflation expectations), which could see house prices to income ratios worsen slightly for a time, though lower mortgage rates would offset in terms of home ownership costs.

But on the other hand, there is a risk that a more abrupt adjustment in house prices could see house price to incomes reduce. Our current forecasts have house prices to income declining, but not moving too far from current levels, though the exact path is uncertain.

The point is: we don’t see the current crisis, or the dramatic change in the stance of monetary policy that has occurred, as being a game changer for housing affordability in either direction.

There are always winners and losers in terms of policy impacts, though. For those saving for a deposit (and for savers generally), lower interest rates will mean it takes longer to build up a nest egg.

However, if interest rates were not lower, income prospects would be worse for many people. And the hardship and inequalities that arise from people not being able to find employment should not be underestimated.

RELATED ARTICLES

NZ Consumer

What Negative Interest Rates Could Mean for You

NZ Business