NZ Consumer

Financial Wellbeing: Why Your Relationship With Money Really Matters

Emily Ross

ANZ’s latest Financial Wellbeing survey of adults in New Zealand reflects new ways of understanding and measuring financial wellbeing.

It turns out, if you want to assess a person’s financial wellbeing, there is a simple question you can ask them.

‘Can you pay your bills on time?’

It’s a powerful question because many people, regardless of how much they earn, will struggle to do this. Then there are other people who behave very differently, consistently squirrelling away funds regardless of how meagre their cash flow is.

Saving for a rainy day is something a lot of New Zealanders take seriously.

According to the latest ANZ Financial Wellbeing: A survey of adults in New Zealand report, released on 8 December 2021, more than half of the New Zealand population (56%) make sure there is money available for unexpected expenses or emergencies and 37% have set up their accounts so that their savings are put aside automatically.

Almost one-third (34%) of New Zealanders have stashed away a nest egg of more than six months of saved income for that rainy day.

It is not all good news though, as 12% of New Zealanders reported having no savings.

The latest survey of 1,505 adult New Zealanders demonstrates that financial wellbeing is a complex blend of socio-economic circumstances, behaviour traits, attitudes towards money and life stage.

The survey investigates the ‘enablers’ and ‘blockers’ of financial wellbeing, examining behaviours, skills and attitudes to money.

'Can you pay your bills on time?’

Many people, regardless of how much they earn, will struggle to do this. Other people consistently save regardless of their income.

The report is a continuum of a body of financial wellbeing research that ANZ began in Australia in 2002.

In New Zealand, ANZ has been collaborating with the Te Ara Ahunga Ora/Retirement Commission (formerly the Commission for Financial Capability), working to better understand the financial knowledge of New Zealanders for many years.

More recently, it has participated in the bank’s financial wellbeing surveys involving adult Australian and New Zealanders across diverse life stages and locations.

Financial wellbeing is defined as the extent to which someone is able to meet all their current commitments and needs comfortably, and has the financial resilience to maintain this in the future.

International pioneer of financial capability and wellbeing research Professor Emeritus of Personal Finance and Social Policy Research at the University of Bristol, Elaine Kempson explains that financial wellbeing is a combination of two factors.

“It’s how much money you’ve got, and it’s what you do with the money you’ve got.”

The survey groups the New Zealand population into four categories.

The top 25% were considered to have no worries (financial wellbeing score >80-100)

47% were doing OK (financial wellbeing score >50-80)

20% were getting by (financial wellbeing score >30-50)

The bottom 8% were considered struggling (financial wellbeing score 0-30).

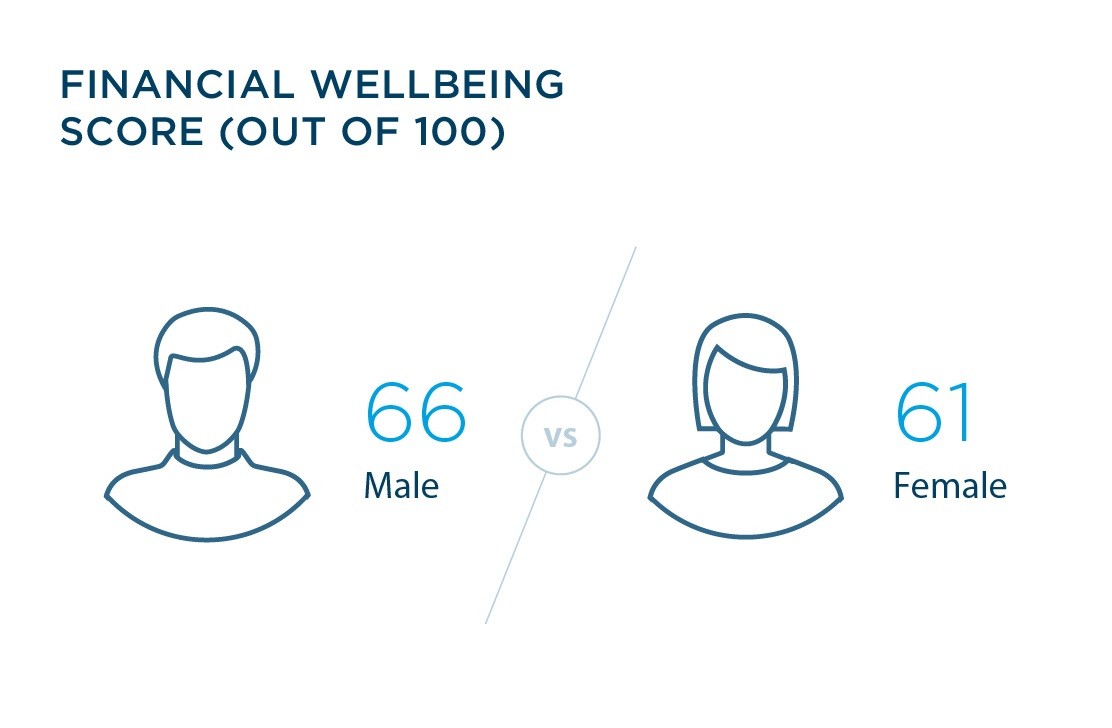

New Zealanders have an average financial wellbeing score of 63 with men scoring higher (66 out of 100) than women (61 out of 100).

Men generally scored above average and women scored below average for whether they were feeling comfortable about their financial situation, their financial resilience and their security for the future.

Both had average scores for meeting everyday commitments.

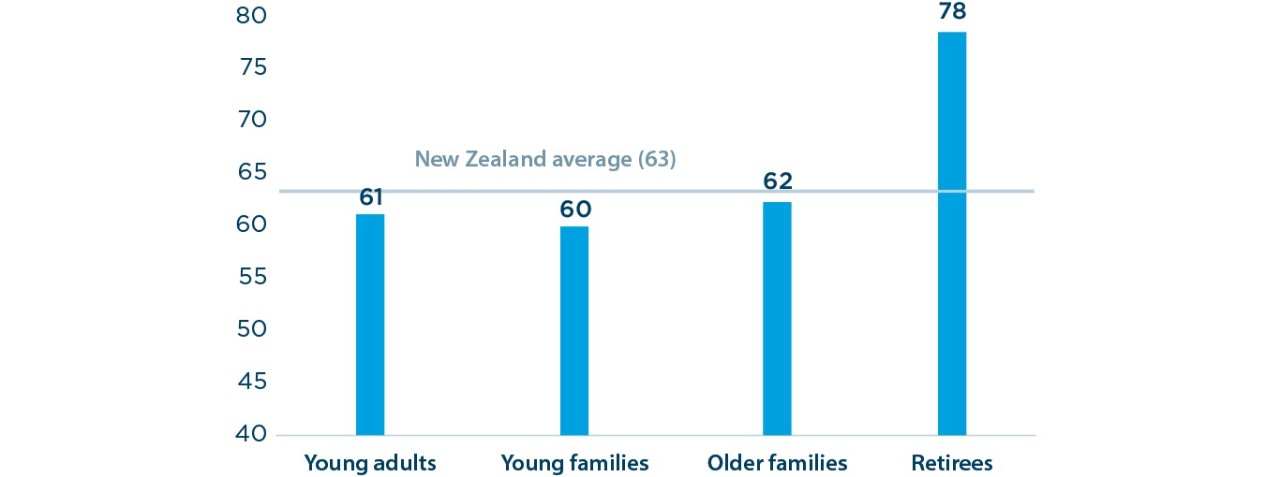

Retirees have the highest financial wellbeing scores of 78 and young adults and young families averaging 61 and 60 out of 100 respectively.

Notably, fully retired New Zealanders over 65 years of age have much higher average financial wellbeing than all other groups, 15% above the national average at 78 out of 100, evidence of how life events and life stages need to be taken into consideration when assessing financial wellbeing.

There has been an evolution in how we understand the concept of ‘financial wellbeing’.

For the first time, a fourth dimension of financial has been included – feeling secure for the future, with investment behaviour included as an additional financial behaviour with a direct impact on financial wellbeing.

How well do the following describe your future financial security?

'I have saved (or will be able to save) enough money to last me to the end of my life.'

'I am securing my financial future.'

The survey found that the lower a person’s financial wellbeing, the higher was their anxiety about their future financial situation.

While 59% of New Zealanders generally felt optimistic about the future generally, 43% of New Zealanders felt anxious when thinking about their future financial situation.

Two fifths (41%) felt they had saved (or will be able to save) enough money to last to the end of their life.

Fourteen per cent of people with no worries felt anxious about their future financial situation, compared to 43% of people doing OK, 64% of people getting by and 80% of people struggling.

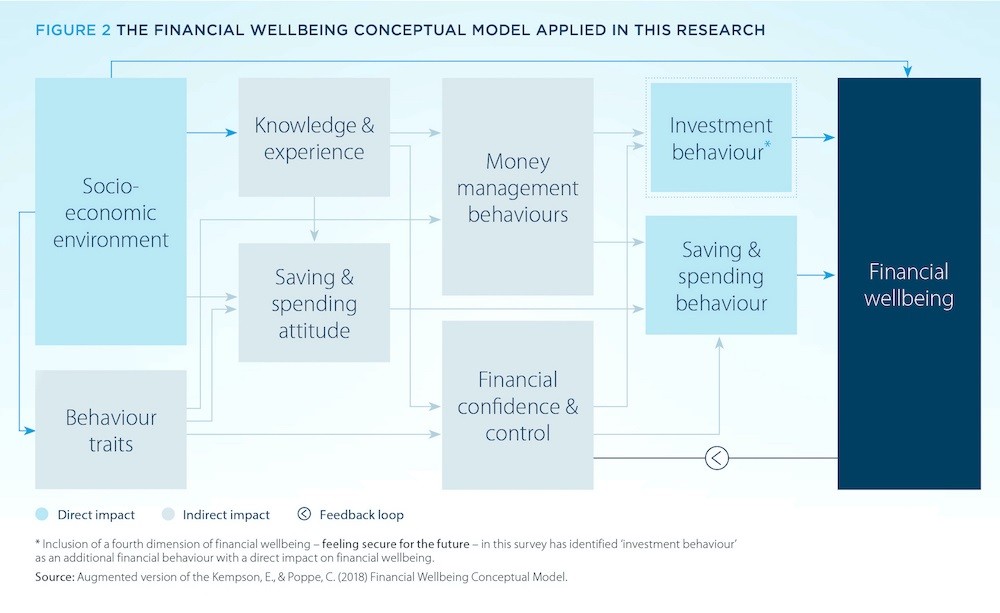

The survey uses a combination of the highly regarded Kempson et al. revised financial wellbeing model and structural equation modelling (SEM) to better measure and analyse the relationships and causal linkages between each of the different drivers of financial wellbeing.

This approach enables a better explanation of what affects financial wellbeing and the different pathways to financial wellbeing.

“The addition of the structural equation modelling of the latest data is a huge contribution to our understanding,” says Professor Kempson.

“It enables us to assess the overall effects of individual factors on financial wellbeing, including indirect as well as direct ones.”

Importantly, the new model is able to more accurately measure the total impact of socio-economic factors and life events on financial wellbeing.

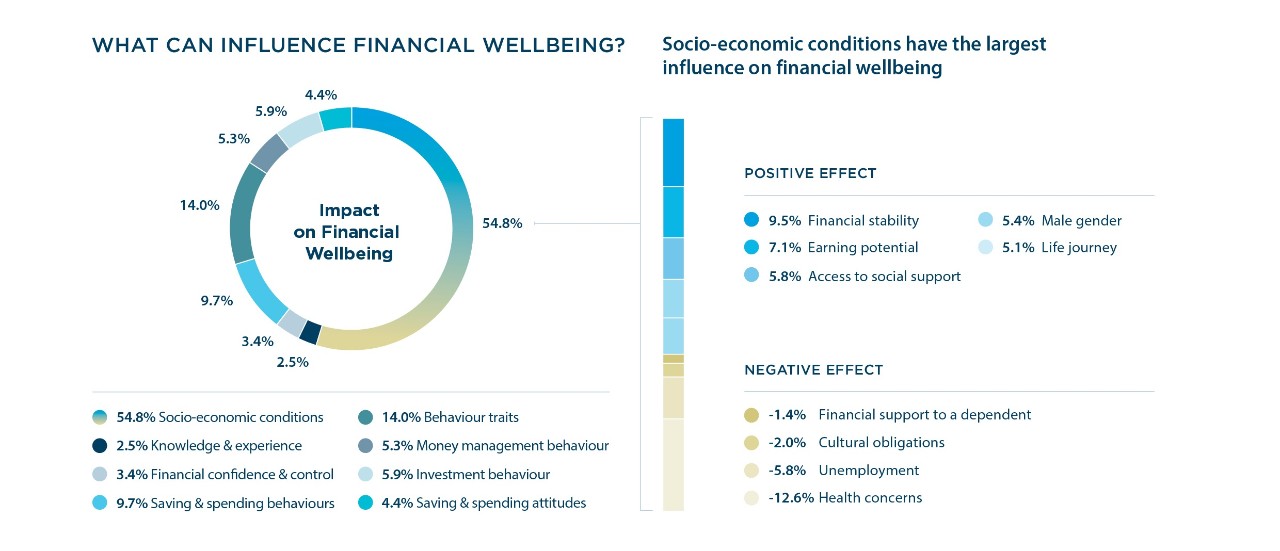

Socio-economic factors account for 54.8% of a person’s overall financial wellbeing.

Health, financial stability, earning potential and unemployment are the most significant socio-economic factors affecting financial wellbeing.

Fleur Howard, Chief Executive Good Shepherd New Zealand and a member of the New Zealand report’s Steering Committee highlights the importance of this socio-economic metric.

“It’s incredibly important for policymakers to understand the shift in thinking about financial wellbeing and capability that has happened in recent years – particularly that no matter how much financial capability support we provide, a person’s socio-economic context is key to their financial wellbeing, by a massive 54.8%,” she says.

“Policymakers need to have more of a long-term focus on the socio-economic environment people are living in.”

This latest conceptual model of financial wellbeing better explores the relationships between these characteristics (health, financial stability, earning potential…) and how they work together to create financial wellbeing.

The model features a ‘feedback loop’, whereby an improvement in financial wellbeing improves one’s financial confidence and sense of control.

“Financial confidence and control still influence financial behaviour which in turn influences financial wellbeing which in turn … and so we have a feedback loop,” says contributing researcher Prescience Research’s David Blackmore.

"So an improvement in financial wellbeing, whatever the original cause, has the potential to be self-reinforcing through the improvement in financial confidence and control.”

Financial behaviours, whilst not as influential as socio-economic factors, still have a very important role to play in financial wellbeing accounting for 20.9% of the financial wellbeing score.

Saving and spending behaviours – active saving and not borrowing for everyday expenses and spending restraint – continued to have the strongest influence out of all financial behaviours, directly influencing financial wellbeing; whilst investment behaviours also directly affect financial wellbeing and money management behaviours such as monitoring finances, planning and budgeting, and informed product choice and decision-making influence financial wellbeing indirectly through driving saving, spending and investment behaviours.

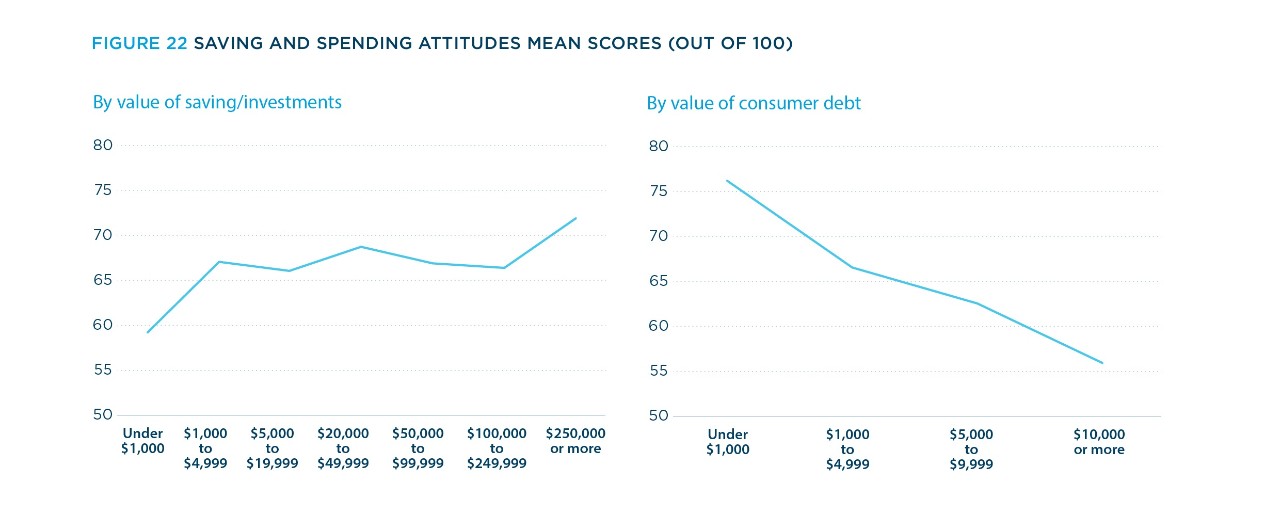

Attitudes to saving or spending have a direct effect on how people save, spend and use credit. Attitudes to saving and spending were positively correlated with the value of savings and investments held, particularly for accumulated savings and investments up to $5,000 and at the high end of over $250,000. Similarly, people with more of a savings mindset had lower levels of consumer debt.

The survey also investigated cultural financial obligations for New Zealanders and how they affected financial wellbeing.

Whether an individual felt they had obligations to support extended family also had an impact on financial wellbeing.

6% of New Zealanders reported that they were providing financial support to extended family.

This was more likely to be the case for younger families with 9% providing financial support to extended family and people running their own business part-time (15%).

This was also more likely for people from a Māori cultural background (10%), Pacific Islander cultural background (22%) and for people from a Māori and Pacific Islander cultural background (12%).

People from a Māori cultural background had an average financial wellbeing of 54 out of 100, significantly lower than the general population. They were twice as likely to describe that their current financial situation was ‘bad’ (30% compared to 15% of the general population) and were also more likely to think home ownership was an unrealistic goal (27% compared to 15% of the general population).

The research was designed to better understand the nuances of individual financial situations and is further evidence for Dr Pushpa Wood, Director, NZ Fin-Ed Centre, Massey University and fellow NZ Steering Committee member that interventions need to take into account the cultural context, needs, locus of control perception and the willingness to learn.

“We have been narrating the rhetoric of ‘one size doesn’t fit all’,” she says, “but I am struggling to find many examples of this being put into practice.”

The 2021 Financial Wellbeing report includes a more holistic look at the drivers of financial wellbeing and includes new areas of questioning to better explain financial wellbeing.

Areas studied include:

· Future financial security

· Digital capability and online scam experience

· Key life events

· Disruptions to the life-cycle such as health and mental health

· Access to social support

· A broader range of behaviour traits including frugality, optimism and goal setting.

For example, the research showed a strong relationship between poor physical and/or mental health and financial wellbeing, that it has more of a bearing on financial wellbeing than a person’s savings and spending behaviour.

People with low financial wellbeing responded that their mental health was fair or poor, 44% for people getting by and 57% of people struggling.

For contributing researcher RMIT University Professor Roslyn Russell, the updated modelling of the drivers of financial wellbeing force us to “widen the lens” of financial wellbeing and recognise the externalities that influence or stymie positive behaviours, “to take account of the context, identify the barriers and allow us to create effective solutions,” she says.

This also allows for better targeting of resources to areas that make the most difference.

This latest financial wellbeing report also includes new insights on how a person’s financial locus of control, the extent to which people feel responsibility for how they manage their money rests with them, affects key behaviours that determine financial wellbeing.

How well does this statement describe you personally?

My financial life is largely outside my control.

Dr Pushpa Wood sees locus control as a critical factor in understanding financial wellbeing. She explains it as “whether an individual believes/perceives that they have control over their destiny or whether it is someone else/external factors controlling their destiny,” she says.

“Each of these perceptions will then influence their approach to financial behaviour and management and will determine whether their behaviour moves towards self-management or handing over this responsibility to someone else.”

According to the survey, 19% of New Zealanders felt their financial situation was largely outside of their control. There was a greater concern for people with low financial wellbeing, with 40% of people struggling and 28% of people getting by feeling their financial situation was outside their control.

Elaine Kempson explains this in terms of informed financial decision-making – as the difference between ‘wanting’ and ‘needing’.

Informed decision-making is a key behavioural trait for financial wellbeing, gathering and weighing up information before making a decision. “It is the opposite of impulsivity in many ways,” says Kempson.

For fellow report Steering Committee Member, Dr Jo Gamble, Research Lead, Te Ara Ahunga Ora/Retirement Commission, people face all sorts of barriers to achieving financial wellbeing beyond lack of financial education and socio-economic factors that can involve both financial (e.g. gender or ethnic pay gaps) and non-financial inequity (like access to housing or mental/physical health facilities), which also need to be addressed.

“And then it gets more complicated when you consider the social norms regarding money that surround an individual (i.e. the role money plays in the family, or in a person’s peer group) as well as a person’s own personality,” she says. “So, finding ways to improve people’s financial wellbeing needs a holistic approach.”

Financial wellbeing research has come a long way from early focus on the premise that was that financial literacy equals knowledge rather than taking into account socio-economics, behaviours, attitudes and other contexts.

According to the modelling in the survey, financial knowledge added just 2.5% to financial wellbeing.

The research has evolved to reflect this. Kempson describes the latest ANZ surveys as an “enormous step forward” in how we understand the drivers of financial wellbeing.

“It has adapted to meet new challenges as we understand better what matters most to people’s financial lives.

Generations to come will be grateful for the wealth of information it provides.”

As understandings of financial wellbeing deepen, and research findings create stronger links to overall wellbeing, the importance of building financial wellbeing and interventions to improve financial wellbeing will only increase.

The big challenge ahead? For Dr Pushpa Wood it’s simple: “We need to really close the gap between ‘what people want to learn’ and ‘what they need to learn’.”

Emily Ross is a content producer and Director of Emily Ross Bespoke.

Dr Pushpa Wood, Fleur Howard, Jo Gamble and Celestyna Galicki were invited to contribute insights as members of ANZ’s external steering committees for this research. ANZ acknowledged their contribution to the research through a donation to their nominated charity.

The views and opinion expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

RELATED ARTICLES

NZ Consumer