NZ Business

Riding High - But Wobbles Expected in NZ Housing Market

ANZ Property Focus assesses the state of the property market in New Zealand, providing investors and prospective homeowners with an independent appraisal of recent developments.

October Overview at a Glance

Summary

Our monthly Property Focus publication provides an independent appraisal of recent developments in the residential property market.

Housing market overview

The housing market is very tight, with inventory of houses on the market at an all-time low. This has added to price pressures, with house prices up 4% over the past three months.

Price increases have been broad based regionally, although there are some reports of softness in the Auckland apartment market. Further price increases are expected in the short term, with the market still tight, but a serious test lies ahead.

Although the economic outlook is a little better in the short term, the recovery is expected to stagnate as we enter 2021, at which point we expect to see some wobbles in the housing market emerge, even with further stimulus expected from the RBNZ. See Housing Market Overview below for more information.

Feature Article: Riding high

The housing market is riding high, with income support having provided a significant cushion, alongside a boost from lower mortgage rates. The removal of loan to value ratio (LVR) restrictions has added to demand but has not been a significant driver of the market – and yet financial stability risks are increasing. A “frothy” speculative element appears to be emerging, with FOMO (fear of missing out) part of the equation.

Buyers are of the view that it is a good time to buy despite being in the midst of an enormous economic downturn, and house prices appear to be moving against the tide of fundamentals from already very elevated levels. That could contribute to a more volatile cycle if a turn in the market comes – particularly if buyers entering the market have high debt to income, making them more vulnerable to income strains.

Macro-prudential policy is likely to be increasingly in the spotlight if current trends continue. The fact is, the housing market does undergo downturns from time to time and homeowners need to be able to ride the wave knowing that sometimes it does get choppy. See Feature Article: Riding high for below for more information.

Mortgage borrowing strategy

Average home loan rates across the four major banks are little changed over the past month. The average 6-month rate is lower, but it is still sufficiently above the 1-year rate that it remains less unattractive, even with our expectation that we see an OCR cut in around 6 months.

Floating is also unattractive and we instead favour the 1-year rate as a proxy for floating, mindful that the likely introduction of a “funding for lending” programme by the RBNZ next month is likely to lead to further mortgage rate reductions.

It is this expectation that makes 2-year and 3-year fixed rates less appealing despite them being at historic lows and not significantly higher than the average 1-year rate. See Mortgage Borrowing Strategy below for more information.

Housing Market Overview

Summary

The housing market is very tight, with inventory of houses on the market at an all-time low. This has added to price pressures, with house prices up 4% over the past three months. Price increases have been broad based regionally, although there are some

reports of softness in the Auckland apartment market.

Further price increases are expected in the short term, with the market still tight, but a serious test lies ahead.

Although the economic outlook is a little better in the short term, the recovery is expected to stagnate as we enter 2021, at which point we expect to see some wobbles in the housing market emerge, even with further stimulus expected from the RBNZ.

Demand strong, price pressures mount

The housing market is extraordinarily tight. Although new listings onto the market have edged higher as we have entered spring, continued strong demand has seen inventory of unsold houses on the market fall toan all-time low – adding to price pressures.

In the month of September, prices rose 1.8% m/m to be up 4% over the past three months – an exceptional increase in the midst of a global pandemic and economic downturn.

Recent buoyancy in sales and prices will encourage some potential sellers to take the plunge and list their homes. But with the starting point for listings so low, the market should remain tight, consistent with further price pressures in the short term.

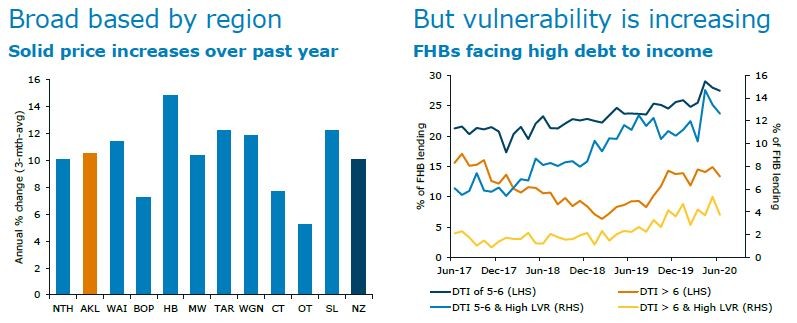

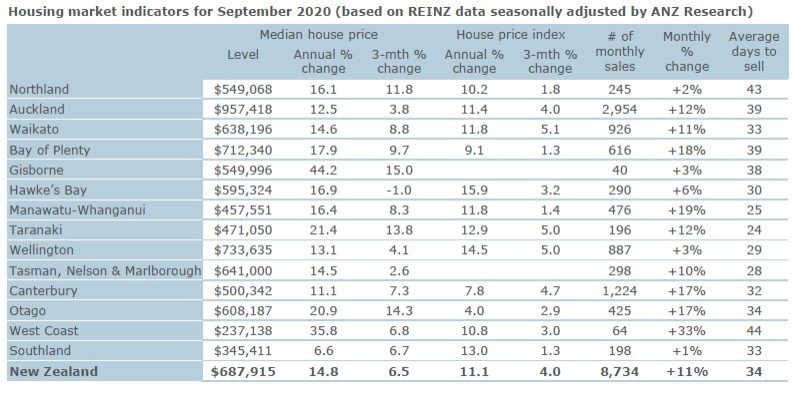

Broad-based across regions Regionally, price pressures have been reasonably broad-based over the past year (figure 1).

Looking at the last three months in particular, strong price rises have occurred in Waikato (5.1%), Wellington (5%), Taranaki (5%) and Canterbury (4.7%). Otago is the only region where house prices are still below March levels (down 4%), driven by weaker prices in Queenstown, but prices in the region have now started rising again (up 2.9% q/q).

Anecdotally, there are pockets of weakness in the Auckland apartment market, which isn’t surprising given the lack of foreign students. But nonetheless, Auckland house prices are up 4% over the past three months, in line with price rises for the country as a whole.

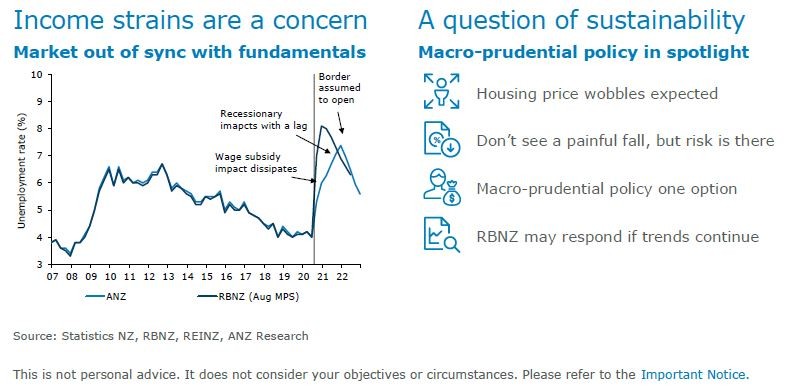

With tightness in this market still evident, some further price rises are likely in the near term (figure 2), but this pressure is not expected to be sustained and Auckland prices may be particularly vulnerable if the housing market were to turn.

Building activity strong

Strength in the housing market and low mortgage rates have continued to support home building and renovations. After a period of disruption due to lockdown restrictions, the construction industry is very busy again.

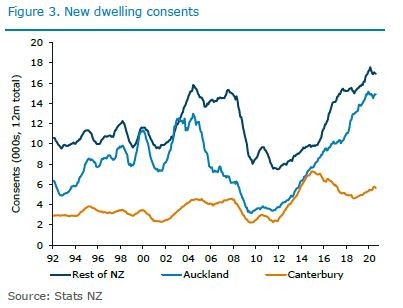

Housing Market Overview

New dwelling consents are 6% below where they were in February, but are still elevated, supportive of a strong residential construction pipeline in the next 6-9 months (figure 3).

Economic outlook a little more positive

The construction industry is the most buoyant sector according to business surveys, and this is not surprising, given the strong housing market and the domestic focus of these firms. Other businesses are finding conditions more difficult, but nonetheless are also starting to feel more positive about the outlook. It now looks like a more solid rebound in activity can be achieved through the second half of this year, alongside a smaller deterioration in the labour market, in no small part due to the support provided by the likes of the wage subsidy.

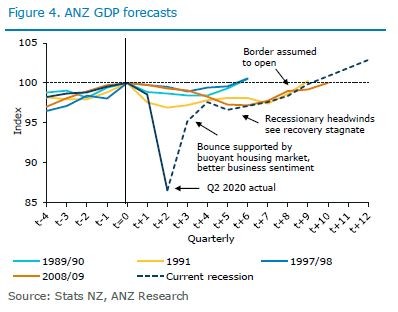

We have upgraded our short-term economic forecasts and now see GDP rebounding a bit more strongly through the second half of this year (figure 4).

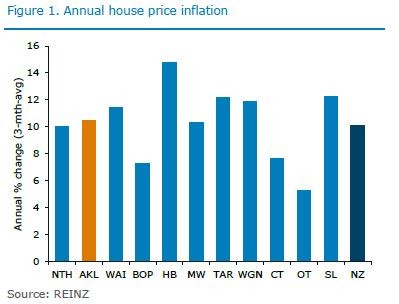

With GDP expected to be a bit stronger, closed border impacts not fully evident yet and the wage subsidy having provided a cushion to date, the unemployment rate is expected to rise a bit more slowly than previously assumed. We expect the unemployment rate to peak at 7½% by the end of 2021.

But the real test is yet to come

A serious test for the economy lies ahead though, with the recovery expected to stagnate into 2021, particularly as fiscal supports roll off, and as the impacts of the closed border become more evident, with domestic tourism unable to offset the loss in international visitors in the summer months. See our ANZ Quarterly Economic Outlook for more details.

As the economy enters a more challenging time as we move into next year, the housing market is expected to experience some wobbles, even with more monetary stimulus expected. Currently, the housing market is moving out of sync with where we see fundamentals (such as income) tracking and the sustainability of the current upturn is increasingly coming into question, especially to the extent that it’s driven by speculative behaviour. See Feature Article: Riding high for more details.

Further declines in mortgage rates are expected to provide some further offsetting support for the market through next year. In November, we expect the RBNZ to announce the deployment of a Funding for Lending Programme (FLP), providing money cheaply to the banks in order to allow retail interest rates to go even lower. See our recent Insight for more details.

Feature Article: Riding high

Summary

The housing market is riding high, with income support having provided a significant cushion, alongside a boost from lower mortgage rates. The removal of loan-to-value ratio (LVR) restrictions has added to demand but has not been a significant driver of the market – and yet financial stability risks are increasing. A “frothy” speculative element appears to be emerging, with FOMO (fear of missing out) part of the equation.

Buyers are of the view that it is a good time to buy despite being in the midst of an enormous economic downturn, and house prices appear to be moving against the tide of fundamentals from already very elevated levels. That could contribute to a more pronounced cycle if a turn in the market comes – particularly if buyers entering the market have high debt to income, making them more vulnerable to income strains. Macro-prudential policy is likely to be increasingly in the spotlight if current trends continue. The fact is, the housing market does undergo downturns from time to time and homeowners need to be able to ride the wave knowing that sometimes it does get choppy.

The housing market is riding high

The housing market has seen a solid resurgence post-lockdown, with the price declines seen in April and May now a mere blip (figure 1). There has been an element of catch-up taking place, but house prices have more than clawed back declines to be up 4½% since March, despite the enormous economic downturn underway. House prices are now 13½% higher than they were in mid-2019.

The economic shock that has been seen to date has had a muted effect on the housing market for a few reasons.

First, lower interest rates have been supportive, with mortgage rates having fallen about 80bps. In normal times, this would usually be associated with house prices rising about 2-2½%. But in a recession it is quite typical for house prices to fall even as interest rates are slashed, due to income losses and uncertainty. But we have seen house prices rise even further than the usual response to lower mortgage rates in normal times, and more quickly too. Some of it is finance maths: at low interest rates, the pass through to asset prices is likely more potent than usual estimates would suggest. But even so, it appears that something else is going on.

The other key factor providing a significant cushion has been income support. Household incomes have been shielded by the wage subsidy and mortgage deferment schemes, while the unemployment impacts of the recession have been muted so far, even as production in the economy has taken a massive hit. This has been crucial for supporting spending, business sentiment and the housing market – though it is important to note it was never a sustainable response and the impacts of the policies will now quickly taper.

Added to that, the suspension of loan-to-value restrictions by the RBNZ at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis will have contributed to housing demand a little, even though the restrictions were not binding for the banking system as a whole. For some buyers, relaxation of the restrictions will have allowed them to at least bid in auction rooms, if not buy. But this effect has been at the edges; it does not appear to be a significant driver of recent housing market strength (with low-deposit lending contained – see below).

Overall low-deposit lending has not increased…

First home buyers and investors have been taking a greater share of new mortgage lending. In September, new mortgage lending was 29% higher than seen on average over 2019, but lending to first home buyers was 39% higher and investor lending 54% higher. That has seen the share of lending going to first home buyers rise to 19.1% from a 2019 average of 17.6%, and the investor share rise from 19% to 23%.

Yet overall low-deposit mortgage lending (defined as deposits of less than 20%, ie 80%+ LVRs) has not increased, even as house prices have risen further. First home buyers tend to have smaller deposits and investor loans tend to be considered more “risky”, but the overall share of buyers at 80%+ LVRs (low deposits) has not risen. It is sitting at about 11% – the same as it was over 2019. Banks remain cautious.

Where there has been an increase is in investor lending with deposits in the “medium-high” risk range with a 20-30% deposit (figure 2). This is a trend that bears watching. Indeed, the RBNZ has indicated that it is watching these trends closely.

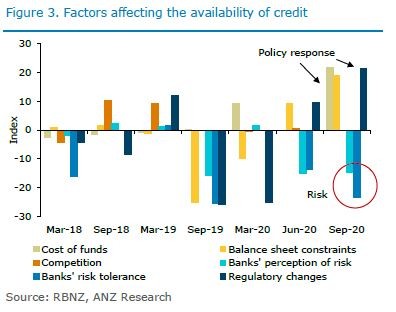

But overall, there does not appear to be a concerted move towards high-risk lending by banks, nor on the other hand, a material tightening in credit standards taking place. The RBNZ credit conditions survey for September showed that credit standards for

mortgages have changed little (figure 3).

Banks are checking incomes more carefully, but on the other hand, they are now applying lower interest rates to test serviceability, which represents a freeing up of credit, all else equal.

Policy changes have played a role in keeping credit flowing to the economy. Although banks quite rightly perceive that there is more risk out there, and they are wary about it, the RBNZ’s responses – lowering the OCR, embarking on the LSAP (boosting deposit funding) and removing LVR restrictions, among others – have contributed to the fact that there has not been a material tightening in credit conditions (figure 4).

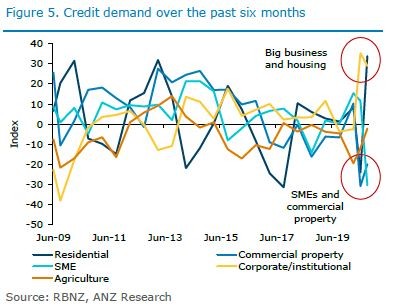

Overall, it appears that credit demand is in the driver’s seat. But there’s a two-speed response happening – home buyers and large businesses are keen to take on credit, but small businesses are not (figure 5).

…and equity positions are good, for now

In aggregate, homeowners appear to have good cash deposits or existing equity positions, with overall equity associated with housing turnover increasing in recent months (figure 6).

Some sellers may be downgrading and using home sales to pay down debt. Anecdotally, cashed-up kiwis returning home from abroad may also be contributing to the jump in equity. But population flows overall have actually been very weak, so it’s not clear how significant this has been. It is possible that cashed-up buyers have been contributing to price pressures, but

there is no way to verify that in the data.

For first home buyers, accumulated savings, KiwiSaver withdrawals and potentially redirected travel funds are helping support new purchases, plus the bank of Mum and Dad may be helping in some cases. In the month of August, $127 million in KiwiSaver funds were withdrawn for first home purchases, plus many buyers presumably had other cash to contribute. New lending worth ten times that went to first home buyers in the same month, and 42% of that lending was with a smaller than 20% deposit – about the usual proportion.

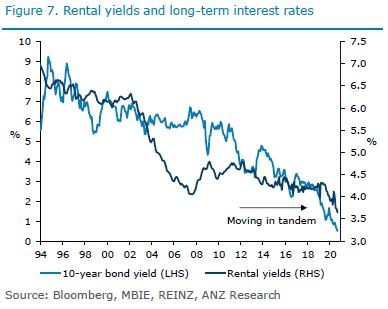

Meanwhile, investors have been able to use the equity they have built up on the back of house price rises to purchase additional homes. This has become more appealing given low returns on other assets. As house prices have risen, rental yields have fallen (figure 7), with rents having risen only 1% over the past year but house prices up 11%. A fall in rental yields and other asset returns is to be expected when interest rates fall, because investors move between different assets in search of return, suppressing yields.

But a speculative dynamic is emerging

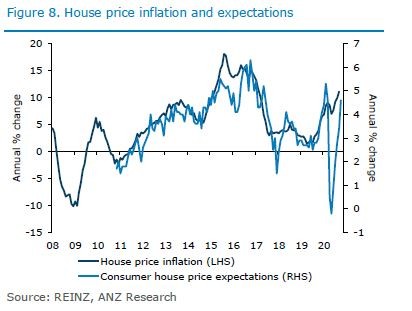

House price expectations are increasing and they appear to be lagging actual house price developments at present (figure 8). Recent strength in the housing market appears to be fuelling expectations that price rises will continue, stoking demand in a way that has the potential to become self-fulfilling. Anecdotes and reports of a strong market are no doubt adding to that. This isn’t an unusual dynamic for the housing market, but seeing it at play in a recession is certainly something new.

And even more telling is the fact that ASB’s Housing Confidence survey shows that the proportion of households who think it is a good time to buy a house is at net 21%, despite the enormous economic downturn underway.

This is the highest level since 2012, when the housing cycle was starting to take off and a speculative element was beginning to take hold of the market. Eventually, an expansion of risky borrowing led to the implementation of loan-to-value ratio (LVR) restrictions by the RBNZ.

And yet, when the ANZ Roy Morgan consumer confidence survey asks households whether it is a good time to buy a major household item, the answer? “Heck no”.

Sentiment here is improving but remains at recessionary levels. So are we going to have a whole lot of freshly bought houses with no appliances in them? No. The fact that households are simultaneously saying it’s a great time to borrow $500,000 to buy a house but a terrible time to borrow $500 to buy a fridge speaks to the uneven nature of this economic shock.

Lower income earners are bearing the brunt of the COVID-related job insecurity. But many of them were locked out of the housing market long ago.

The expectation that house prices will continue to rise (even if perhaps by less than before) – and perhaps a realisation that renewed LVR restrictions may be looming – is leading to the perception that an opportunity to enter the market mustn’t be missed.

And that demand is stoking house price expectations further. Those same expectations of capital gains are driving investor demand too, even as increased regulation has made property investment less attractive. Forecasts that interest rates will move even lower are likely adding to these expectations.

FOMO appears to be part of the equation

Effectively, there appears to be an element of FOMO (fear of missing out) driving the market, based on an assumption that house prices will keep increasing. This dynamic has the potential to contribute to frothiness in the market that ultimately cannot be sustained – adding to financial stability risks. The fact is, history – especially further back than the past few decades – tells us that house prices do indeed fall from time to time and that the market can turn very quickly.

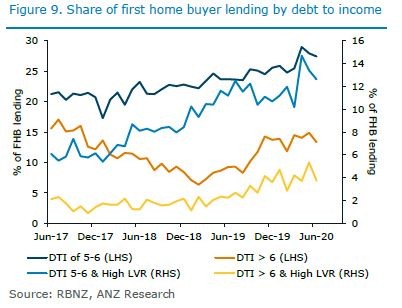

Expectations that interest rates will remain low are encouraging borrowers to enter the market with debt levels that are high relative to their incomes, even if deposits are decent. We have seen first home buyer activity increase, and those buyers are more likely to be in vulnerable debt-to-income categories, even if their equity positions are good. Indeed, there has been an upward trend in the share of buyers in riskier debt-to-income buckets over the past year (figure 9).

But buyers are vulnerable to income shifts

Exuberance, if it continues, could contribute to a more pronounced housing cycle, adding to risks that the housing market has further to fall if it eventually turns. This risk is accentuated to the extent that buyers who are entering the market have high debt-to-income ratios, making them more vulnerable to income strains.

Income strains are a typical pressure point for the housing market in a recession. Good equity positions (low LVRs) make it less likely that homeowners will go into negative equity if house prices fall.

But if someone’s income dries up, then they may not be able to service their mortgage, no matter how low mortgage rates might seem right now. In the extreme, this can lead to significant financial hardship, fire sales and nasty feedback loops between house prices, spending and credit supply.

House prices and household debt levels are already very high in New Zealand, making the market vulnerable to a disorderly correction at some point. This isn’t a new risk by any means, but an outright housing boom in a recession would certainly up the ante.

Housing affordability is a serious social and economic problem in New Zealand that requires some mix of lower prices and/or enormously higher incomes to resolve.

Seeing prices drift lower as a result of more supply, weaker population pressures or adjusting regulation would be socially desirable, even if it would come at a cost to existing homeowners. But triggering a demand-choking painful correction in house prices would most certainly not be a win.

To be clear, it is not our expectation that such a painful correction in house prices will occur, but the risk is there, and increased speculative behaviour that could expose borrowers to income strains adds to it.

We question the sustainability of the upturn

Unemployment looks set to rise, even if by less than previously expected, and some households will face more challenging times ahead. As such, we are becoming concerned that the housing market appears to be increasingly moving out of step with fundamentals, like rents and incomes – particularly given our expectations for where those fundamentals are headed.

Looking forward, we expect that the economic recovery will stagnate, that closed border impacts will become more evident, and that income strains will increase – and ripple well beyond low-income earners. It is our view that these effects will see some wobbles emerging in the housing market as we enter 2021, even as mortgage rates move lower. Our current assumption is that we see another strong quarter to finish the year, but that house prices will fall 4% next year, before recovering. This is a smaller, later fall than our previous forecasts.

Of course, the outlook is highly uncertain and the strength in the housing market to date has surprised us. It is possible that further declines in mortgage rates have a more potent effect than we assume and the housing party goes on longer. But there is also the possibility that increased income strains, reduced population pressures, and a shift in expectations lead to a more abrupt adjustment in house prices than incorporated in our central forecast. Policymakers will be cognisant of the risks on both sides.

Financial stability in the spotlight

Recent signs that financial stability risks might be creeping higher will see macro-prudential and broader housing policy increasingly in the spotlight, if those trends continue.

Interest rates are not the right tool to address financial stability risks; prudential tools are. “Leaning against the wind” (keeping interest rates a little higher than otherwise on financial stability grounds) has been shown to lead to suboptimal societal outcomes. The housing market is one of the (many) channels that monetary policy works through, but longer-term trends in house prices tend to be largely outside the control of central banks.

That’s not the same thing as saying there is nothing to worry about, though. Increasingly, we are moving to a world where “big bang” monetary stimulus at the onset of the crisis needs to be replaced by a more nuanced approach, with the case for ever-increasing stimulus becoming less clear, especially with impacts and risks associated with new unconventional tools unknown.

We think more stimulus will be deemed necessary by the RBNZ, in the form of an FLP and then negative OCR. But at some point, adding more stimulus could boost the housing market more than is necessary for monetary policy objectives to be achieved. A considered, gradual approach is likely to be increasingly required as the recovery progresses, with scope to pause and see how the economy is tracking.

The best policy at the RBNZ’s disposal for addressing financial stability concerns is prudential policy. Micro-prudential policy relates to the solvency and liquidity requirements faced by banks to ensure they can cope with unexpected shocks. On this score, New Zealand banks have excellent buffers to weather any storm and protect the interests of both shareholders and depositors.

RBNZ’s proposals to increase capital requirements still further in July next year would mean the banks would have even more “skin in the game”, but it could come at a cost by increasing the price of credit, or curbing its availability, at a time when a fragile recovery is still in infancy. In that respect, it’s not the case that bigger system buffers are always better, and timing broad changes carefully is very important.

Macro-prudential policy provides an extra overlay to the micro-prudential framework by responding to financial stability risks in a more cyclical or targeted fashion, such as responding to an increase in risky lending that might lead to an unhelpfully pronounced house price cycle. The RBNZ has a number of these tools currently at its disposal, including LVR restrictions, countercyclical capital tools, and adjustments to the core funding ratio.

At the start of the COVID-19 crisis the RBNZ relaxed some of its counter-cyclical tools, loosening the core funding ratio and suspending LVR restrictions for a year. The aim was to protect against a tightening in credit supply and that appears to have been successfully avoided. But at the time the RBNZ was anticipating marked falls in house prices and activity. Now with signs of a “frothy” dynamic emerging in the market, albeit in its infancy, the RBNZ will be alert to evolving risks and may respond with a macro-prudential overlay.

If wobbles in the housing market emerge next year as we expect, then the RBNZ would be more likely keep LVR settings as they are to ensure that credit keeps flowing, since downturns in the market are typically accompanied by increased caution on the part of both lenders and borrowers.

But if the market continues to run hot and macro-prudential policy is deemed necessary, the obvious response would be to reinstate LVR restrictions. Responding with broader tools, like the counter-cyclical capital buffer, could risk choking non-housing lending though, so not all macro-prudential policy options would be deemed appropriate.

The RBNZ plans to review whether to reinstate LVR restrictions in March next year. The case would be particularly clear if there was a surge in low-deposit lending between now and then.

But implementing LVRs isn’t the only option, and it may not be effective or indeed the best response. High debt-to-income ratios (like high LVRs) can be a significant source of vulnerability in a downturn, and risks tentatively appear to be building in this area.

The RBNZ does not currently have a mandate to implement debt-to-income (DTI) restrictions, but its macro-prudential policy powers are currently under review as part of The Reserve Bank Act Review.

A case could be made for expanding the RBNZ’s powers to include these sorts of tools should they be required in the future, even if they are not needed any time soon. But it’s political, because DTIs make it harder for first home buyers to get on the ladder.

Broader policies are also needed to address our long-term housing affordability challenge, like adjustments to regulations limiting land supply and building, and ensuring that population flows are sustainable (once the border opens) given limited home building capacity and infrastructure. Such policies can help from a financial stability perspective too.

Lack of responsiveness of housing supply and huge swings in population can lead to house prices becoming unaffordable, but can also lead to more exaggerated house price cycles overall. There are no easy answers, but doing nothing isn’t a solution either.

Mortgage Borrowing Strategy

This is not personal advice. The opinions and research contained in this document are provided for information only, are intended to be general in nature and do not take into account your financial situation or goals.

Summary

Average home loan rates across the four major banks are little changed over the past month. The average 6-month rate is lower, but it is still sufficiently above the 1-year rate that it remains less unattractive, even with our expectation that we see an OCR cut in around 6 months. Floating is also unattractive and we instead favour the 1-year rate as a proxy for floating, mindful that the likely introduction of a “funding for lending” programme by the RBNZ next month is likely to lead to further mortgage rate reductions. It is this expectation that makes 2-year and 3-year fixed rates less appealing despite them being at historic lows and not significantly higher than the average 1-year rate.

Our view

Average mortgage rates are once again little changed over the past month, and once again the only change of any note was the circa quarter percentage point fall in the average 6-month rate. The 1-year rate remains the cheapest rate.

Although we expect the RBNZ to introduce a “funding for lending” programme next month and to cut the OCR below zero in April, which in turn should see most mortgage rates move gradually lower, we continue to favour the 1-year term as a proxy for floating.

Odd as it may seem to fix for a year ahead of a period when we expect mortgage rates to generally fall, with the 1-year rate so much lower than floating and 6 month rates, it is still likely to be cheaper overall.

Our sense that the 1-year tenor is the most attractive is borne out in breakeven analysis. Logical as it sounds to perhaps fix for 6 months now with a view to re-fixing again in six months, the maths just doesn’t stack up.

As our breakeven table shows, the 6-month rate would need to fall from its current rate of 3.58% to 1.46% over the next six months for the interest bill on a pair of back-to-back 6-month terms to be less than the interest bill on a 1-year term at 2.52%.

That could happen, but it seems a stretch considering that most forecasters expect a much smaller move in the OCR. For example, we expect a 0.50% point fall in the OCR in April.

Staying on floating would be even more expensive in the meantime, and one would need to be confident of some fairly large falls in rates in months to come for it to be worthwhile remaining floating with a view to fixing later. If, for example, one had a $100k mortgage and elected to remain floating at 4.51% instead of fixing for 1 year at 2.52%, the extra interest is around $166 per month.

If you stayed on floating for, say, 3 months, it’d cost you an extra $497. To be better off in the long run, you’d need to recoup that by fixing at a better rate in three months’ time. And if you wanted to fix for one year, to recoup the $497, the rate would need to be 0.50% lower.

We could see a move like that over the next three months, but it’s more than what we have seen in recent months, and it’s a lot to expect ahead of an OCR cut that’s not likely until April. It is this maths that stands behind our preference for the 1-year rate, and if one’s mortgage is split over a number staggered terms, that is a close proxy for being floating, albeit at more competitive rates.

With longer-term fixed rates also very low, it is worth asking: is now a good time for fix for longer? When considered purely from a cost perspective, we don’t think it is. Certainty has a place and some borrowers value it – but ahead of what is likely to be further declines in mortgage rates and a long period of rates remaining low, that certainty comes at a high price.

Download Full Report

related articles

NZ Business

Supporting Farmers Through Tough Times

NZ Business