NZ Insights

Making Sense of the Reserve Bank's Bag of Tricks

Sharon Zollner, Chief Economist

Liz Kendall, Senior Economist

David Croy, Senior Strategist

ANZ NZ Ltd.

Summary

With the OCR near zero, the RBNZ has had to work with a new bag of tricks since the COVID-19 crisis hit. This month we provide a simple explainer of how these tools work and affect the economy.

The latest tool to be introduced is the bank Funding for Lending Programme (FLP), which is aimed at lowering interest rates on mortgages and other bank loans.

It’s hard to know what impact it will have, but it might lower interest rates by another 20-40bps. Looking forward, a test for the economy lies ahead.

The outlook for policy is finely balanced though, and developments in the housing market are one of many possible factors that could tip the balance towards erring away from a negative OCR.

A negative OCR is a mind-bending idea, and could have some negative consequences, but for most people on the street the implications would be the same as for a regular cut in the OCR.

Another one from the bag of tricks

At the November Monetary Policy Statement (MPS) earlier this month, the RBNZ announced the deployment of a Funding for Lending Programme (FLP). The FLP represents a new, unconventional means of stimulating the economy with monetary policy.

The Large Scale Asset Purchase Programme (LSAP) implemented earlier this year (sometimes called “Quantitative Easing” or “QE”) is another one of these new, unconventional measures. Beyond the LSAP and new FLP, the RBNZ also has other options in its bag of tricks, including possibly taking the Official Cash Rate (OCR) negative.

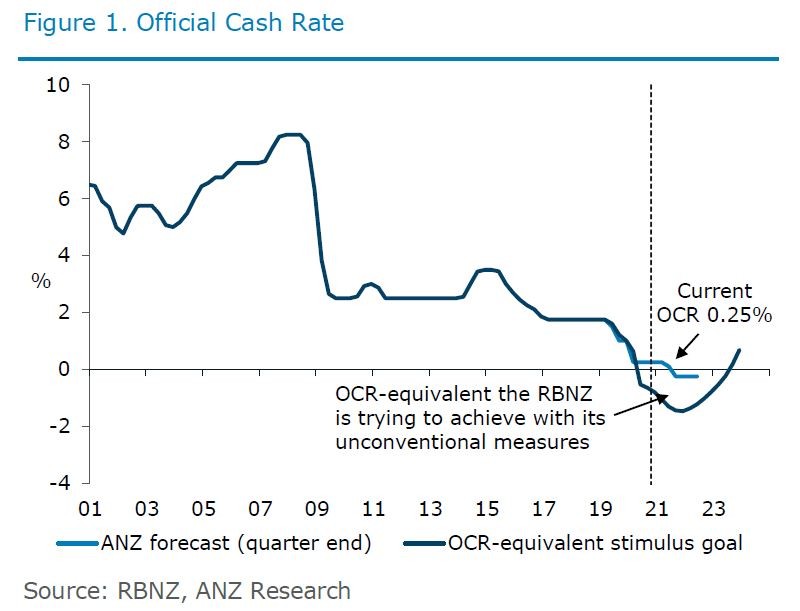

Usually, the RBNZ would lower the OCR to stimulate the economy, sometimes very significantly in times of severe downturns. But after dropping the OCR 75bps in April to 0.25%, scope to take the OCR lower was limited (figure 1).

New tools were required.

The reason the OCR had so little room to move at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis was because interest rates have been trending down for a number of decades, reflecting a range of structural factors (see our introduction to a negative OCR for more).

This long-run downward trend in interest rates has been largely outside of the RBNZ’s control, though the success of inflation targeting globally has contributed. The RBNZ elicits shorter-term movements in interest rates around this longer-term trend.

The RBNZ’s first move into unconventional territory was to introduce the LSAP in March, along with a number of other measures to support market functioning and the flow of credit in the economy.

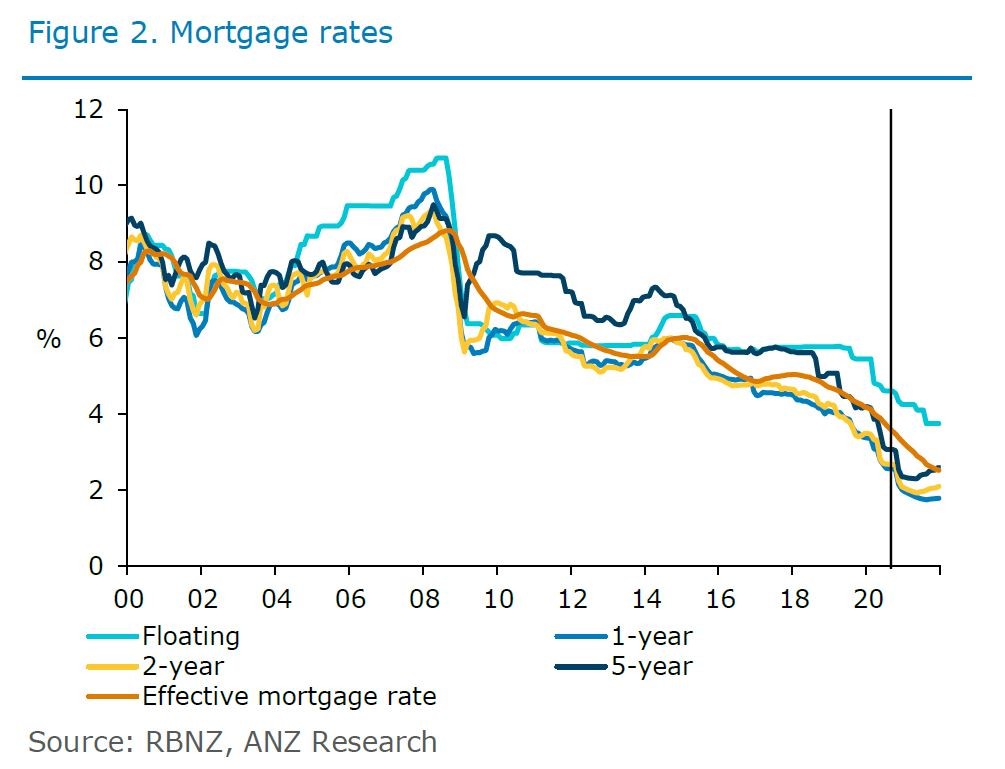

The LSAP has been reasonably effective at lowering market interest rates, which have fallen about 200bps. However, retail interest rates (on mortgages and other bank loans) have moved only a little more than the 75bp drop in the OCR (figure 2).

This difference reflects the fact that the LSAP is aimed at wholesale markets, while retail rates are influenced by a range of other factors, such as bank funding costs and availability, balance sheet considerations, risk appetite and assessments, and competition.

A drop in the OCR would usually tend to have a reasonably strong effect on both retail and wholesale rates, though again, the pass-through to retail rates is not necessarily one-to-one, reflecting the range of factors above.

For now, the current LSAP programme has run its course in terms of its impact, given that there are limits to how many bonds the RBNZ can (and would want to) buy.

But at the November MPS, the RBNZ deemed that it needed to provide a bit more stimulus to the economy, in order to meet its employment and inflation targets.

And to do this, the RBNZ would like to see retail interest rates move lower. Enter the FLP from stage right.

FLP, what was that?

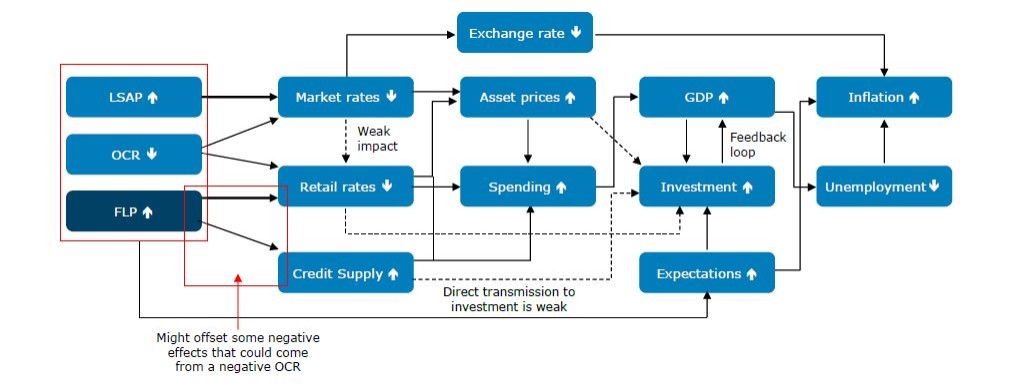

Essentially, the FLP can be thought of as a retail version of the LSAP (though there are technical differences), with the direct aim of seeing retail interest rates move lower.

By offering funds at the OCR, the programme lowers banks’ funding costs and increases banks’ confidence in their ability to raise funds.

This puts downward pressure on retail interest rates and potentially increases credit supply, with flow-on effects to the economy.

The scheme’s measure of success will be the impact it has on household and business borrowing costs, rather than how much of the available funds are borrowed.

Behind the curtain

The key elements of the scheme are as follows:

- The RBNZ offers banks three-year loans, lent out at a floating interest rate (the prevailing OCR).

- Banks pledge existing high-quality assets (“securities”) to the RBNZ in exchange for cash.

- This swap doesn’t technically impact total funds; it just makes them cheaper. Additionally, the scheme can encourage banks to lend.

- The amount of available funding is linked to the size of banks’ balance sheets, with some additional funding available if banks expand lending.

- Initial loans will be available for access for 18 months and loans linked to the additional caps for a following six months.

Will it do the trick?

It’s hard to say how effective the FLP will be in lowering retail interest rates and boosting the economy.

lthough bank funding costs will be lower, the impact on retail interest rates will depend on banks’ expectations and financial positions (banks’ “net interest margins”– the margins between lending and deposit rates – have been trending down), along with broader competitive pressures and the strength of incentives to lower deposit rates.

We estimate that we could see retail interest rates fall by 20-40bps, but it is quite uncertain. This will have some impact in stimulating the economy.

However, based on the current outlook, the FLP may not be quite enough to achieve the medium-term outlook the RBNZ is looking for, meaning a negative OCR is still on the table.

See our November MPS Review for more details.

How does the FLP work?

Under the FLP, the RBNZ lends directly to banks at a cheap rate (the current OCR).

This lowers the funding costs faced by banks and also provides a funding backstop that means banks can compete a bit less for other sources of funding (like deposits) and interest rates on these can be priced lower.

This in turn leads to lower retail lending rates (for mortgages and other bank loans).

The availability of FLP funds is also partially linked to loan growth.

This may encourage banks to lend and increase credit supply. And because the FLP provides a funding backstop, this could allay fears of future funding constraints (there are none at present), perhaps making banks feel a little more confident to lend as well.

Lower retail rates combined with a possible expansion in the supply of credit has flow-on impacts through the economy. For more on how the FLP works, see our FAQ here.

More up their sleeve

The RBNZ has signalled that it could take the OCR lower or even negative if the economy needs even more of a boost. However, it is now looking less likely, given the resilience that has been seen in the economy.

A negative OCR is a mind-bending possibility but for most people on the street it would work in the same way as a normal OCR cut. Retail rates (on loans and deposits) would be unlikely to go negative, so it would mean lower, but not negative, interest rates.

The implications in financial markets would be a bit more complicated though, since wholesale interest rates and some deposit rates for large corporates would go negative. Generally speaking, the economy would be affected in much the same way as with a regular cut in the OCR.

That said, at a certain point, a negative OCR can have diminishing or even counter-productive effects on the economy – potentially more than offsetting other stimulatory effects from the likes of a lower exchange rate.

This is because as well as potentially damaging confidence, a negative OCR can squeeze bank profits and reduce the availability of credit.

A squeeze on bank profits can occur because there are limits to how far deposit rates can fall without severely impacting customer retention – at a certain point people would rather take their money out as cash and store and insure it!

If lending rates are under pressure but banks cannot lower their deposit rates further, this will squeeze net interest margins.

One of the additional benefits of the FLP is that it can potentially offset some of the perverse effects that a negative OCR could have on bank profits and credit supply.

Because of the FLP, banks have an additional source of cheap funding, giving them confidence to lower deposit rates a bit more, reducing some of the margin squeeze.

However, the FLP can only offset so much of this impact, meaning there is still a point when a lower OCR can become problematic.

For this reason, we think there is a limit to how low the RBNZ would be willing to take the OCR, perhaps in to -0.5% or -0.75%.

We also think that because of these (and potential other) negative effects, the hurdle to take the OCR negative is a bit higher than for a regular OCR cut – and if a negative OCR was deployed, a gradual, feel-your-way path lower is probably more likely than a very abrupt shift.

The big reveal

Although the RBNZ has previously signalled that a negative OCR is a very real possibility, it is now looking less likely and may not occur at all.

All forecasters have been surprised by the economy’s resilience to the current downturn, which means urgency for further stimulus has diminished. Partly this is because incomes have been supported by the wage subsidy, but that’s now finished.

The economy faces a test in coming months, especially because tourism arrivals are very seasonal, and it is through the summer months that we will feel the pinch there.

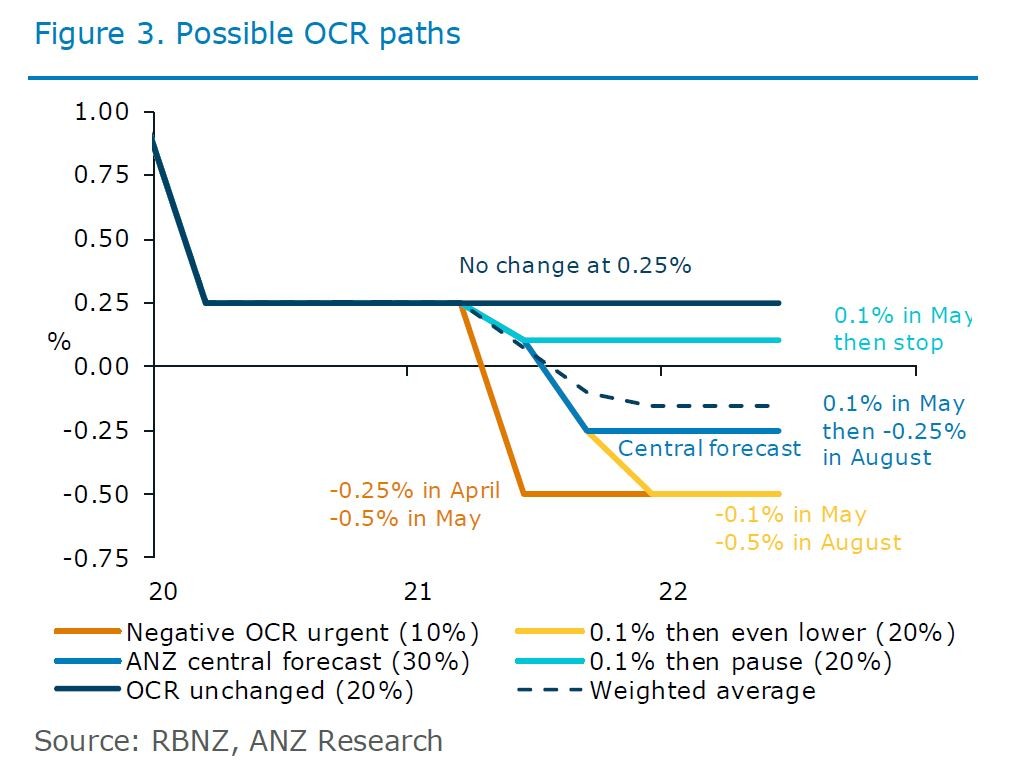

On balance, it looks to us like the economic recovery will stagnate as we head into 2021, and that in time the RBNZ will deem that a little more stimulus is needed.

Our current forecast is that by May next year a little more stimulus will be deemed helpful and the OCR will be lowered to 0.1% (or somewhere very close to 0% but slightly above).

Then by August, we think some continued disappointment in the data flow will mean that the hurdle to a negative OCR will be met, with a further cut in the OCR to -0.25%.

The policy outlook is highly uncertain though and has become more finely balanced, depending on developments.

The case appears to be building to err on the side of not employing a negative OCR, but we will continue to wait and see how developments unfold. We can imagine things playing out in a number of different ways (figure 3).

See our recent ANZ Insight: Weighing it up – Possible OCR paths for more on possible scenarios and our ANZ Data Wrap for key data and milestones affecting the outlook.

We expect that the shine will come off the housing market in coming months, but the outlook is uncertain. A better outlook for the housing market than we expect would reduce the need for the RBNZ to take the OCR lower.

Smoke and mirrors

The RBNZ has recently come under scrutiny for the impact that lower interest rates are having in stoking house price inflation.

Lower interest rates have certainly played some role in pushing house prices higher on the way to boosting the economy, and stimulus from the FLP and potentially a lower OCR will provide continued support.

But this is a natural consequence of monetary policy; longer-term housing affordability challenges aren’t something the RBNZ can fix (see our recent ANZ Property Focus)

The RBNZ has done what is necessary to shore up the outlook for inflation and employment – and on that score, policy has been very effective, which means that the case for further stimulus has significantly diminished.

Conditions are nowhere near as bad as they could have been.

This week, the Minister of Finance weighed into the public discussion around the impact of low interest rates on house prices, suggesting that the RBNZ remit include a consideration to avoid unnecessary instability in house prices.

This idea is likely to form part of a broader discussion about the issue of high house prices and it is unclear if it will gain any traction.

Under this proposal, the primary goals of price stability and maximum sustainable employment would remain unchanged. House prices would be of lesser concern. In reality, under the proposal, policy setting wouldn’t actually be much different.

Consideration for house prices already forms a key part of policy deliberations for the RBNZ, since developments in the housing market have implications for the broader economy, including the outlooks for inflation and the labour market, and given considerations for impacts on financial stability.

It’s true that the odds of a negative OCR have reduced, but that’s a consequence of broader economic developments, including in the housing market, not the proposal that the RBNZ remit be changed.

To the extent that the housing market remains buoyant and this is supportive of the broader economic outlook, the hurdle to further easing will be higher – but that would have been true anyway.

That means that any change in remit would have little effect on the policy in practice or the outlook, unless a monetary policy decision was a line-ball call.

Certainly, we don’t think it would have changed how policy has played out this year at all, nor does it affect how we think about the outlook for the OCR at present.

That’s the way it should be too. International evidence suggests that keeping interest rates higher than what would be consistent with the Bank’s primary objectives (in order to lean against high house prices and financial imbalances) actually leads to worse societal outcomes through job losses, income strains and the like.

That’s not to say that monetary policy doesn’t have costs, trade-offs, side effects and constraints. It does. That’s why each policy decision has to be weighed up carefully to achieve the best outcomes possible, even though they may not be perfect.

It’s also why good fiscal, regulatory, and prudential policy are so important – to help address the problems monetary policy cannot solve.

One thing that could help would be an expansion of the RBNZ’s toolkit to alter macro-prudential policy in response to financial stability risks.

The RBNZ is proposing to re-introduce loan-to-value restrictions, but there is also scope to expand the toolkit to include the likes of debt-to-income (DTI) caps.

Although this would make it difficult for some to enter the market, it could help to curb demand and limit some of the riskier lending that has accompanied recent strength in the market.

Putting the spotlight on monetary policy to address rising house prices misdirects attention away from where it is urgently needed: addressing the inadequate responsiveness of housing supply and other structural issues in the market.

The RBNZ cannot control these settings, but the Government can. Something needs to be done, but focus should be on policy changes that can actually make a meaningful difference.

RELATED ARTICLES

NZ Business

Sweet Deal – NZ-EU FTA a win for primary producers

NZ Insights