NZ Insights

Property Focus: Off the Beaten Track

Liz Kendall, Senior Economist, ANZ NZ Ltd.

David Croy, Senior Strategist, ANZ NZ Ltd.

Sharon Zollner, Chief Economist, ANZ NZ Ltd.

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.1331.1024.jpeg)

SUMMARY

Globally, housing markets have generally beaten expectations through the COVID - 19 crisis, in part due to a policy response that has been large and synchronised.

But the New Zealand housing market has been an outlier, supported by – and contributing to – our strong economic recovery to date, which has been underpinned by our successful health response and effective fiscal and monetary policy.

Relative to history, the recent episode has been different too.

Although the current housing upturn shares some similarities with the 2000s, maintaining momentum for such an extended period appears unlikely this time around.

While momentum can be self - propelling to some extent, acute housing unaffordability, very high debt levels, macro - prudential policy tightening and credit constraints look set to weigh in time, and that will likely slow the rate of housing price inflation.

However, it may take time for the market to turn and, until that happens, affordability and debt levels could become even more stretched.

GLOBALLY, HOUSING HAS WEATHERED THE PANDEMIC REMARKABLY WELL

The onset of the COVID - 19 pandemic changed the economic outlook dramatically both here and abroad. When we looked down the barrel of this crisis it was unclear how large the economic fallout would be – all we knew was that it wasn’t going to be pretty.

There was enormous uncertainty surrounding virus developments, the duration and impact of lockdowns, how people would respond to uncertainty and lower incomes, and how effectively the Government and RBNZ would be able to cushion the blow.

Forecasts for GDP and other economic variables were revised down dramatically in early 2020 when the virus hit – including forecasts for the housing market.

Incomes were expected to experience a massive blow, unemployment was forecast to rise dramatically, and house prices were widely expected to fall – as has tended to be the case in previous downturns. During the initial (level 4) lockdown, house prices declined very slightly, largely reflecting the market’s inability to function over that time. Those declines now seem like a distant memory.

Since coming out of the initial lockdown, GDP has recovered strongly in New Zealand and the housing market has boomed.

The defining feature of New Zealand’s economic outlook over the course of 2020 was our success at eliminating community transmission of COVID - 19.

Because of this, New Zealand was well placed to weather the economic impact of lockdown.

Disruption here was not prolonged and the immediate fiscal response was rapid and generous, cushioning incomes.

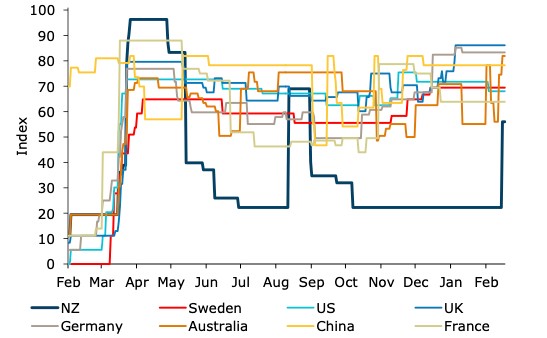

We have since been able to live and operate relatively freely (figure 1) and have begun our economic recovery far sooner than in other countries that continue to count a severe human and economic cost.

Figure 1. Oxford stringency index

Source: Oxford University

Yet there is more than just our COVID success underlying the housing market boom.

Despite continuing community transmission and rolling lockdowns in other countries, robust housing markets have been a global phenomenon.

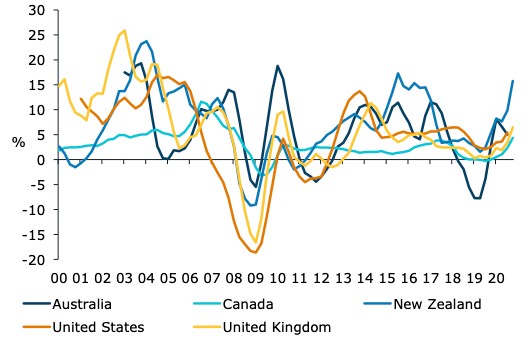

Over the second half of 2020, solid house price increases have been seen in a range of countries that we typically compare ourselves to – although not to the same extent as in New Zealand (figure 2).

Figure 2. Selected global housing markets

Source: ABS, StatCan, REINZ, SPDJI, Nationwide, Bloomberg, Macrobond, ANZ Research

Policy response has been large and synchronised

The most striking theme underpinning global housing markets has been the large and synchronised policy response, particularly monetary policy.

To the extent that there was conventional headroom available, policy rates were lowered, and many central banks – including our own – used unconventional monetary policy measures to drive interest rates down further.

Here in New Zealand, the Official Cash Rate was lowered from 1% to 0.25% in an emergency move in March 2020 and the Large Scale Asset Purchase Programme (“quantitative easing”, or “QE”) was introduced a week later.

Additionally, the Reserve Bank removed LVR restrictions and undertook a range of measures to ensure credit was able to flow freely in the financial system.

More recently, the RBNZ has also introduced a bank Funding for Lending Programme to facilitate further downward pressure on mortgage rates.

Globally, a swift and sizable monetary response was implemented to support economic recoveries and shore up the outlooks for unemployment and inflation.

As a result, central bank balance sheets increased significantly as asset purchases were conducted, suppressing financial market yields (see our ANZ November Property Focus for an explainer on how these unconventional tools work).

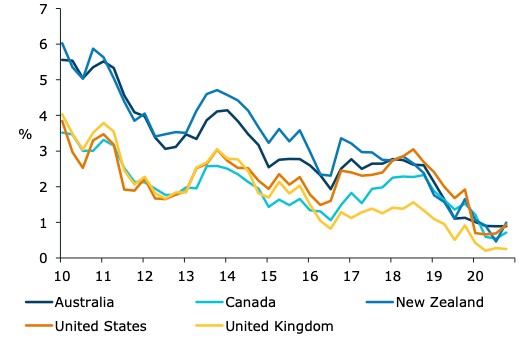

This boosted liquidity in the financial system and saw global bond yields fall in sync (figure 3). Monetary policy works in a number of ways. One key channel is by boosting asset values, including house prices.

Through this and other channels, monetary policy has been undeniably effective at stimulating the economy, with flow-on effects to consumption, construction and confidence.

At the same time, other policies have ensured that bank funding has been plentiful and encouraged credit flow – further bolstering the housing market.

Figure 3. Selected global 10-year government bond yields

Source: Macrobond, BoC, RBNZ, Fed, BoE, Bloomberg, Macrobond, ANZ Research

In New Zealand, building activity was already very strong going into the crisis.

Post-lockdown, the construction industry has been grappling with capacity constraints and a further increase in demand.

Housing spending and confidence has also been supported.

That boost in momentum for these pockets has helped to offset underperforming industries like tourism, retail, and services where conditions are more difficult, and could worsen from here.

These same offsets have been evident in other countries, though to smaller degrees.

That reflects the challenge other countries have in offsetting the impacts of longer lockdowns and greater social and economic disruption.

Globally, governments have also embarked on a synchronised fiscal policy response too.

Fiscal policy is providing financial support for those whose livelihoods and jobs are being affected by the crisis, though the size and impact of this has varied by country.

To the extent that policies have supported incomes, these measures have helped cushion global housing markets.

NEW ZEALAND’S HOUSING MARKET HAS HAD ADDITIONAL SUPPORT

In New Zealand, fiscal measures to support incomes have been particularly potent, in part due to the relatively short duration of our lockdowns.

These measures included the wage subsidy, COVID-19 Income Relief Payment, and other measures to support affected businesses and workers.

These policies were expensive and unsustainable on a long-term basis. However, they were able to smooth household incomes through the lockdown phase of the crisis and keep people in employment.

The net effect has been the avoidance of a vicious feedback loop in which incomes, employment and spending could have plummeted and been more permanently affected.

With incomes largely intact, the economy was well positioned to bounce back when the restraints were removed.

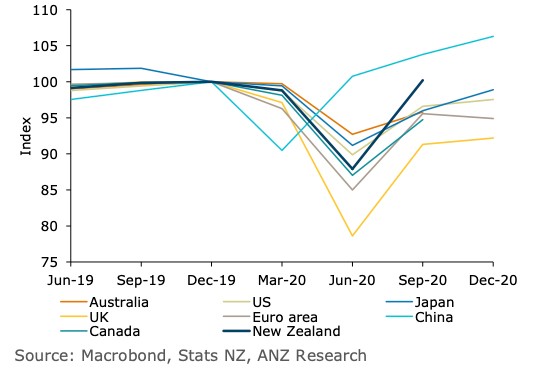

So far, New Zealand has seen a swift recovery in GDP from lockdown-induced disruption (figure 4), with fewer job losses than in other countries (figure 5) – contributing to the stand-out performance of New Zealand’s housing market.

Income support, the fall in interest rates and mortgage deferment schemes all worked in tandem to shore up cash flow and confidence, supporting housing demand and spending more broadly.

Overall, these policies have been more effective than expected – proving an effective stop-gap. That reflects a successful health response and rather generous schemes being in place.

We haven’t come out completely unscathed. Some firms and workers have endured tremendous challenges resulting from the closed border. And we are not out of the woods yet.

Figure 4. GDP levels (Q4 2019= 100)

Source: Macrobond, Stats NZ, ANZ Research

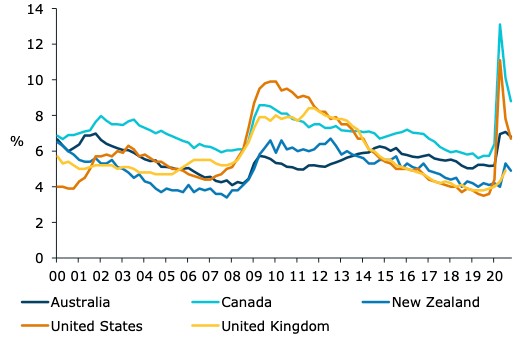

Figure 5. Selected unemployment rates

Source: ABS, StatCan, Stats NZ, BLS, ONS, Bloomberg, Macrobond, ANZ Research Note: The UK unemployment rate is artificially low because the 5.3m people on furlough are not technically defined as unemployed, masking the true impact of COVID-19 on jobs.

While the virus remains rampant globally, there is always a risk that the return of COVID-19 community transmission could see activity disrupted again.

The most recent community cases identified this week (in mid-February) are a reminder of that. So far, relative to other countries, we have been exceptionally fortunate in terms of both health and economic outcomes.

However, if required, we still do have fiscal ammunition to pull out a powerful policy offset in the form of the wage subsidy if required.

STRENGTH IN OUR MARKET HAS BEEN RECORD BREAKING

Momentum in New Zealand’s housing market has been extraordinary, exacerbated by tightness in the market, with very low listings, an emerging speculative dynamic, and rising house price expectations.

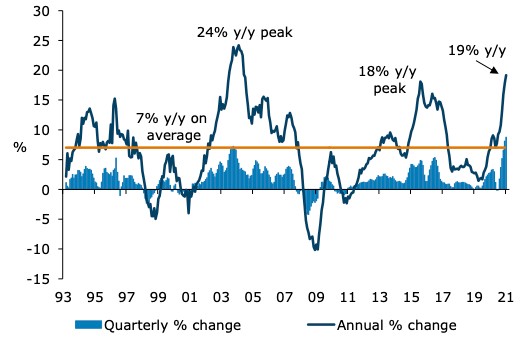

In the December quarter, house prices rose 7.7% q/q – the strongest pace since RBNZ data began in 1992.

Recent price rises have been reminiscent of the early 2000s; so far the upturn has been shorter, but it has been sharper (figure 6).

The experience of the 2000s shows us that momentum in the housing market can be difficult to stop in its tracks, especially when expectations become selffulfilling and risk aversion reduces.

In the early 2000s, New Zealand house prices increased for 26 consecutive quarters (March 2001 to September 2007) to be up 217%.

Figure 6. New Zealand house price inflation

Source: REINZ

COULD WE BE SEEING A SIMILAR EPISODE TO THE 2000S HERE?

The current housing upturn shares similarities with the upturn of the 2000s. Back then, as now, lower interest rates played a role, risk aversion was low, credit was readily available, the issues of inadequate supply that plague our market now were fast developing, and a speculative, self-reinforcing dynamic was evident.

However, there are noteworthy differences between now and the 2000s.

- Unlike in the 2000s, interest rate increases do not appear imminent. Although cost-push inflation pressures are significant, that’s the kind of inflation central banks prefer to look through, and there are still plenty of challenges ahead. Interest rates look set to be supportive of the market for a while yet, whereas the upturn of the 2000s was met by a steep rise in interest rates to keep inflationary pressures under control. Down the track, the market will have to adjust to a gradual return to more normal monetary policy settings. That means higher interest rates eventually, even if they are expected to remain very low by historical standards. But normalisation isn’t likely to be on the cards until the RBNZ’s targets are firmly in view and downside risks have abated, meaning continued easy settings over the remainder of 2021 at least. On our current forecasts, the RBNZ doesn’t embark on policy normalisation until 2023, but upside risks could see this brought forward.

- Immigration, a historic driver of New Zealand property prices, is very weak, in stark contrast to the 2000s. Anecdotally, the return of some cashed-up Kiwis may have been a support to parts of the market but, ultimately, current rates of population growth do not suggest a sustained worsening in the supply-demand balance as was seen in the 2000s. Instead, the rate of building is already very high and looks set to outpace population growth – an encouraging development given the legacy of underbuilding and lack of supply responsiveness that would take years, and bold policy changes, to correct.

- Greater regulation and market forces now represent a greater “handbrake” as well, helping to contain frothiness in the market. Banks are not reliant on flighty short-term funding and are now required to hold higher levels of capital, which means expanding lending is costlier than it was in the 2000s. There are greater limits on lending to riskier portions of the mortgage market, particularly with loan-to-value restrictions returning 1 March. And banks are naturally more cautious than in the 2000s when it comes to the likes of servicing assessments – partly due to the global experience then, but also given the fact that house prices and debt are already high. Indeed, debt-toincome levels are much higher than ever before.

- Incomes are not growing at anywhere near the same rates as they were in the early 2000s. Unemployment is expected to rise further whereas it remained very low in the 2000s.

At some point, the acute and worsening unaffordability of housing must weigh on the rate of house price inflation. That is especially given the unsustainable disconnect between soaring house prices and stagnant income growth (figure 7).

Credit constraints are expected to be a headwind at some point too given income prospects, an expected slowdown in deposit growth, and broader bank prudence expected to weigh.

Figure 7. House price to income

Source: REINZ, Statistics NZ, ANZ Research

Nonetheless, the housing market is difficult to forecast and history tells us that it can be a hard beast to rein in once it gets going. It is possible that the current stimulatory environment sees momentum persist.

This could see households become even more stretched, increasing the risk of a significant future correction.

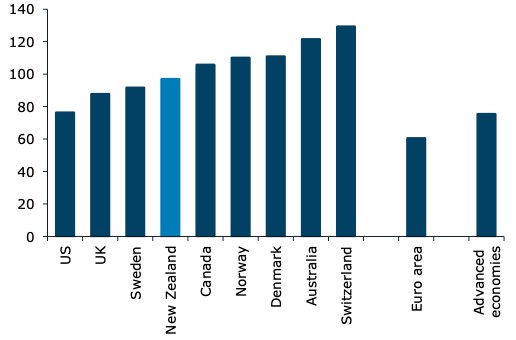

The starting point for household debt was already extremely high going into this, but comparisons with other countries show that these positions could get even worse (figure 9).

There may be structural differences (such as lower interest rates) across these economies that mean higher debt levels are more sustainable.

But the upshot is that it is entirely possible the housing market roars on for some time yet before these metrics act as a constraint, especially if urgent structural policy changes are not made.

Figure 9. Household debt to GDP (Q2 2020)

Source: BIS

MOMENTUM EXPECTED TO SLOW, BUT OUTLOOK UNCERTAIN

The housing market is being affected by offsetting forces and the outlook is highly uncertain. On balance, we think that current strength will not be sustained for an extended period like it was in the 2000s.

Indeed, we may be starting to see the housing market start to cool, with sales returning to more normal levels in January, but it is too soon to tell.

We may see some continued short-term momentum but, over time, fundamental factors like income growth, affordability considerations, weak population growth, strong building, and credit constraints look set to weigh – with the rate of house price inflation expected to slow.

Indeed, the re-imposition of loan-to-value restrictions could be a catalyst for a slowing in momentum, with the RBNZ expecting it will shave 1-2 percentage points from house price inflation and calm “irrational exuberance”.

An eventual normalisation in monetary policy settings will reduce some of the current support to the market too – though that is a story for down the track.

Globally, the synchronisation in the housing market cycle across countries may not last either, and we cannot look to other countries to know what will happen next.

Although global housing markets have moved similarly of late, it is reasonable to expect that outcomes will become more divergent as the initial synchronised boost from monetary stimulus wanes.

To varying degrees, conditions in many economies look set to get worse before they get better.

Risks remain abundant. Economic recovery should provide support once the pandemic is under control, but the threat of eventual normalisation of financial conditions is starting to loom large as asset price overvaluations (whether housing or global equities) start to look more extreme.

It is hard to know how these forces will balance out over time and across countries, especially if the paths to recovery and policy normalisation vary.

New Zealand is likely to continue to forge its own path, given the country-specific factors that have played a role in our recent outperformance.

But given our expectation that house price inflation will slow in time, some convergence to the more moderate rates of growth seen in other countries seems likely. To the extent that growth is credit fuelled, that is probably not a bad thing.

RELATED ARTICLES

NZ Business

Sweet Deal – NZ-EU FTA a win for primary producers

NZ Insights