NZ Insights

Property Focus: Nothing Lasts Forever

Sharon Zollner, Chief Economist, ANZ NZ.

Liz Kendall, Senior Economist, ANZ NZ.

Miles Workman, Senior Economist, ANZ NZ.

David Croy, Senior Strategist, ANZ NZ.

The housing market has had a spectacular run over the past year, fuelled by easy financing conditions, with interest rates low and credit readily available.

But this environment is not expected to last forever. Interest rates are expected to rise, albeit gradually, with longer-end interest rates expected to lift first.

This is expected to pass through only very slowly to costs faced by borrowers, but eventually, debt-servicing is expected to become more expensive.

Meanwhile, abundant bank funding has ensured that credit has been readily available to meet demand, but slowing deposit growth, bank caution and policy changes are expected to see credit conditions become more of a constraint.

Eventually, these factors, alongside affordability limits and other headwinds, are expected to see a slowing in the housing market, though the timing is uncertain, and conditions are expected to tighten only gradually.

To the extent that some in the market are assuming current very easy financing conditions will continue, expectations may be disappointed, potentially weighing on the market more than we currently expect.

Hot housing market supported by easy financial conditions

The housing market has been running rampant since mid-2020, with prices up 22% since May.

In recent months this strength has shown no sign of abating.

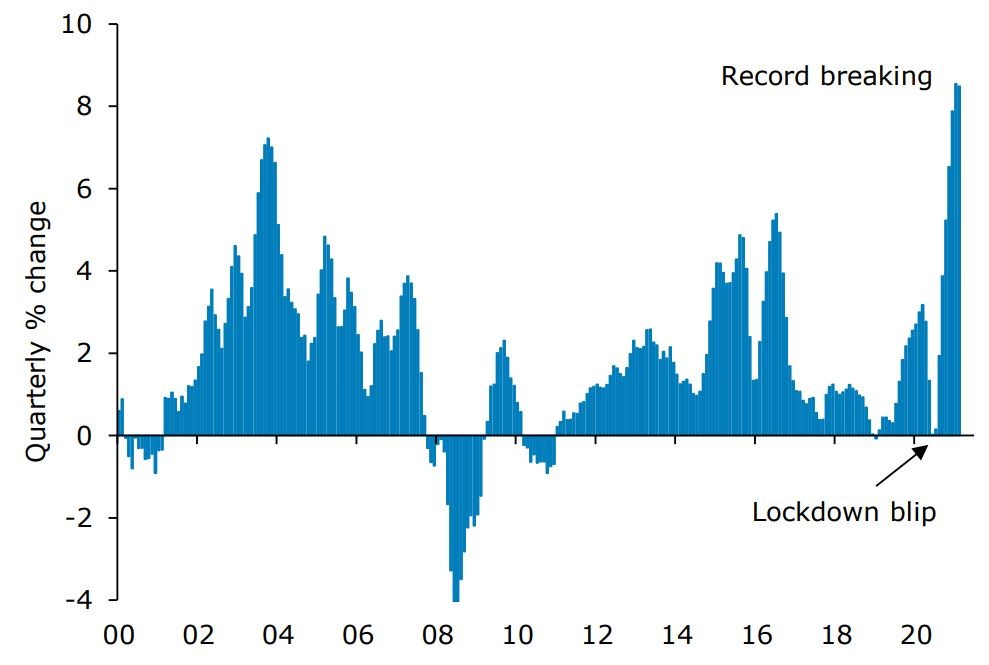

The speed of the recent upturn has been unprecedented, with record-breaking quarterly gains in prices (figure 1).

Figure 1. Quarterly house price inflation

Source: REINZ

A number of factors have supported the recent runup in house prices, but a key one has been very easy financing conditions.

Record low interest rates have boosted demand for housing and credit, and resulting price pressures have been exacerbated by very tight supply in the market.

Meanwhile, abundant bank liquidity, particularly as a result of the RBNZ’s Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) Programme (sometimes called “quantitative easing”, or “QE”), has ensured that credit supply has also been readily available to meet this demand.

A speculative dynamic also appears to have been at play.

Immigration is not likely to have played a large role, given very low inflows overall, but a change in the mix of immigrants may have had an impact in pockets.

Lower mortgage rates have played a key role but are expected to lift eventually

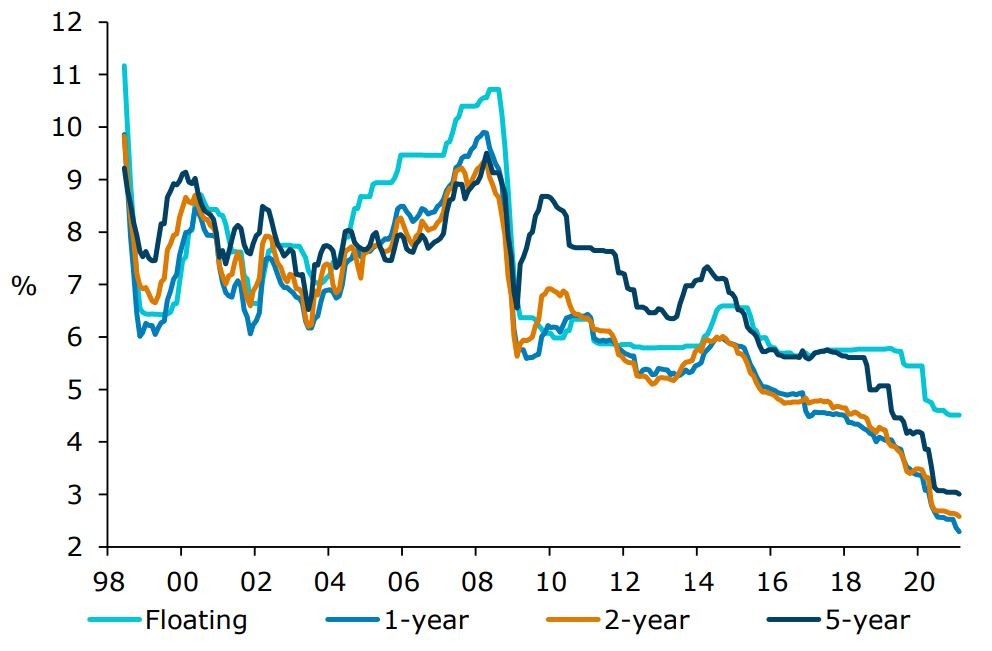

Since February 2020, the lowest mortgage rate (the 1-year) has fallen 110bps, from 3.4% to 2.3% (figure 2).

This has occurred on the back of the RBNZ lowering the Official Cash Rate (OCR) 75bps and deploying unconventional monetary policy tools, including the LSAP and bank Funding for Lending Programme (FLP) – see our ANZ November Property Focus for an explainer on how these tools work.

This has occurred in tandem with other central banks providing stimulus and pushing interest rates lower globally.

Figure 2. Mortgage rates

Source: RBNZ, ANZ Research

The recent fall in mortgage rates is not that large in an historical context.

The lowest mortgage rate available is now about 7%pts lower than it was in the late 1990s.

A number of structural factors (like increased supply of funding globally, lower potential economic growth and declining inflation) have contributed to this steep decline.

But although the more recent ~1%pt dip is not that large in this historical context, it has nonetheless had a significant effect in boosting demand for credit and housing.

Changes in interest rates can have a more potent impact in a low-interest rate environment.

This is because the future benefits of owning a house accrue more quickly (are “discounted” less).

Or put another more intuitive way, future returns everywhere else are super low and that makes scarce assets like housing attractive, driving up the price. In short, what else are you going to do with your money?

So when interest rates are low and supply is constrained, house prices tend to increase more rapidly in response to small changes in fundamentals, while also being more volatile and vulnerable to overshoots.

That’s exactly what we have seen.

Bearing in mind this potent effect of interest rate changes at low levels, recent declines in interest rates can justify the large run-up we have seen in house prices – but only if recent declines are seen to be largely permanent.

This is likely to have been a key part of the recent speculative dynamic that appears to have been at play.

And yet, mortgage rates are expected to increase at some stage, and those making decisions in the housing market should be mindful of this fact.

The OCR is expected to be lifted in time…

With the economy doing much better than expected, the OCR is unlikely to be taken lower from here, provided downside risks do not materialise.

As a result, the current interest rate cycle is now widely expected to have troughed, and focus has shifted from the possibility that the OCR might need to go lower, to when it might go higher.

Current market pricing suggests that the OCR might be lifted from mid next year.

That’s sooner than our own expectations, but the difference isn’t that much relative to the length of a mortgage.

Our current forecasts suggest we could see the OCR being lifted from mid-2023, but the risks are looking increasingly skewed towards sooner than that.

Expectations that the OCR will rise are starting to put upwards pressure on broader shorter-term interest rates, which are a key determinant of bank funding costs and shorter-duration (as well as floating) mortgage rates.

Moves higher in these rates tend to pass through quite quickly to higher borrowing costs, given the short amount of time until borrowers need to re-fix.

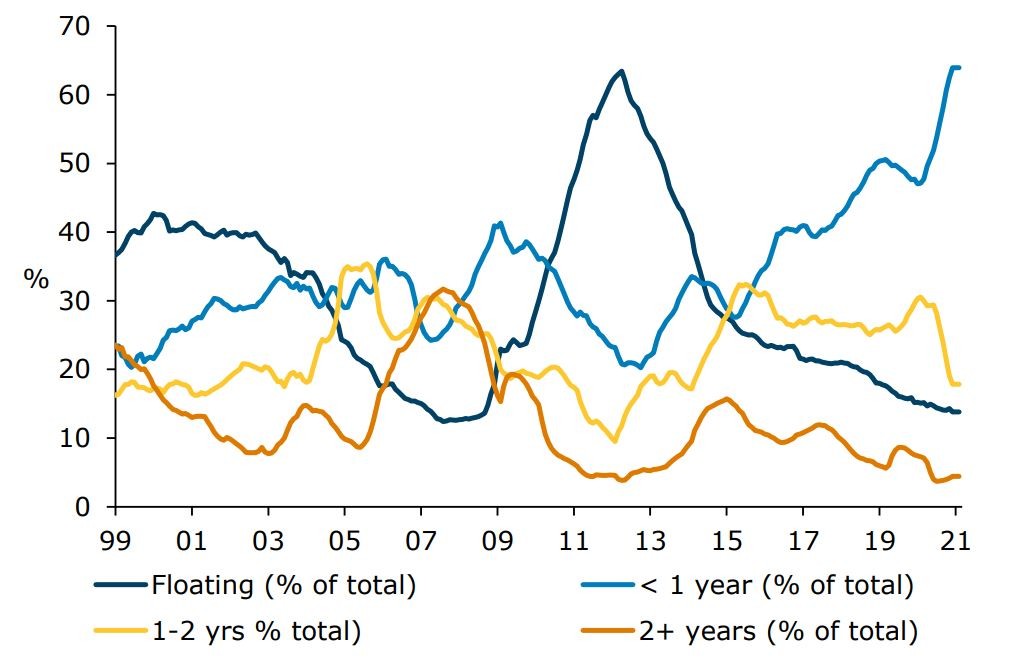

And it is in these shorter-end mortgage rates where a lot of mortgage growth has been happening recently, with almost two-thirds of mortgage lending fixed for one year or less (figure 3).

Figure 3. Share of mortgages

Source: RBNZ

…and long-term market interest rates are rising even faster, primarily on global developments

Although the OCR remains at 0.25% and the RBNZ has signalled that it expects to keep it there “until it is confident that consumer price inflation will be sustained at the 2 percent per annum target midpoint, and that employment is at or above its maximum sustainable level”, longer-term wholesale interest rates have already started to rise.

This reflects:

- higher global interest rates, which in turn have increased on expectations of higher cash rates elsewhere;

- expectations that the next move in the OCR will be up, and not down (with talk of a negative OCR now a distant memory!); and

- less downward pressure on domestic bond yields from the LSAP programme.

The impact of global interest rates has been the most potent factor. New Zealand long-term interest rates (five years and longer) have always been highly correlated with global interest rates.

That’s largely because New Zealand and foreign bonds are substitutes, and there’s a high level of foreign participation in our bond market.

Bond yields – or interest rates – move inversely with the price of the bond, so as the prices of various countries’ bonds move together, the yields do too.

The local connection to global interest rates is also a reflection of the fact that the economic cycle here is also driven to an extent by the global economic cycle.

Right now, global yields are rising as economies overseas recover and the inflation outlook improves.

Domestic considerations, including expectations that the next move in the OCR will be up, do impact our longer-term interest rates, but they tend to be more influential in setting the level, rather than the direction of interest rates.

At the moment, New Zealand has (and typically has had) a higher cash rate (currently 0.25%) than both the US and Australia (both currently at 0.10%).

As a result, the general level of all of our interest rates (from the OCR to the 20-year government bond yield) is a touch higher. Our interest rates will go up and down with US and Australian yields, but off a higher base.

Other domestic policy settings like the LSAP can also influence longer-term interest rates. The whole purpose of the LSAP is to keep downward pressure on long-term government bond yields, which lowers market yields more broadly.

Since it was introduced, the LSAP has suppressed bond yields. But since the programme started, the RBNZ has reduced the size of its weekly bond purchases and shifted the mix of bonds it buys away from longer-term bonds (like 10- 20-year bonds) and towards shorter-term bonds (like 2-3-year bonds).

This means limited downward pressure on longer-term bond yields and swap yields to offset current global pressures.

Mortgage rates set to gradually lift

Higher long-term bond yields will eventually drive mortgage rates higher. As longer-term (say 10-20 year) interest rates rise, this tends to gradually filter along the shorter part of the curve, pulling up 5-10 year rates and, to a lesser degree, 3-4 year rates.

Equivalently, potential rises in mortgage rates are likely to start with 5-year mortgage rates and then filter back down the mortgage curve in time.

But for now, with the OCR on hold and the RBNZ committed to leaving the FLP in place until the middle of next year, there will be much less pressure on very shortterm (say 6-12 month) mortgage rates to rise.

Floating and very short-term mortgage rates tend to move more in tandem with the OCR, and that’s on track to remain at 0.25% until at least the end of this year, if not longer.

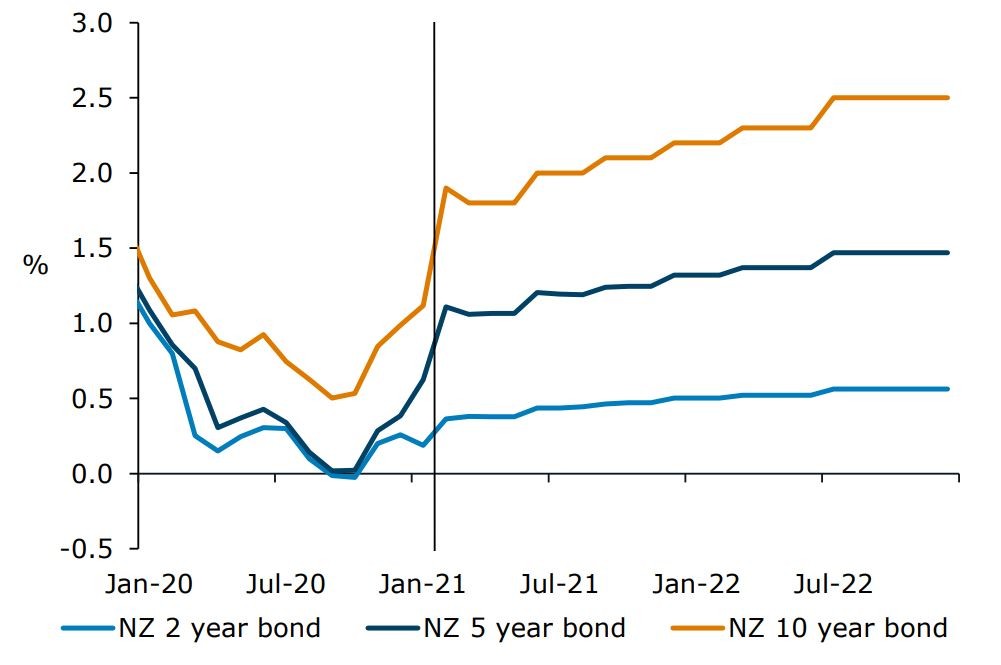

How quickly wholesale interest rates rise and at what point that puts pressure on banks to lift mortgage rates is difficult to say. Wholesale interest rates are already well off their lows (for example, the 5-year government bond yield is around 0.90%pts above its low point of 6 months ago).

There’s been a tiny bit of action in 5-year term deposit rates too, partly reflecting wholesale rates, and partly due to the mortgage borrowing boom having hoovered up an enormous amount of bank funding. We have not yet seen any rise in 5-year mortgage rates.

However, pressures are likely to continue to build, given we expect 5-10-year wholesale interest rates to continue rising over the course of the year, albeit at a more gradual pace than February’s jump (figure 4).

Figure 4. Longer-term bond yields

Source: Bloomberg, ANZ Research

The RBNZ bank Funding for Lending Programme (FLP) will help offset upward pressure on mortgage rates by providing a funding source at cheap rates, with more take-up of the scheme expected in time.

However, this offset is only expected to be partial. We discuss this in more detail later.

Debt-servicing costs impacted very slowly

Overall, mortgage rate increases are expected to be very gradual.

For mortgage borrowers as a whole, the increase in debt-servicing costs that they face will be more gradual still – thanks to the fact that many people are on a fixed rate entered into some time ago, and also for many there may be opportunities to re-fix before rates rise.

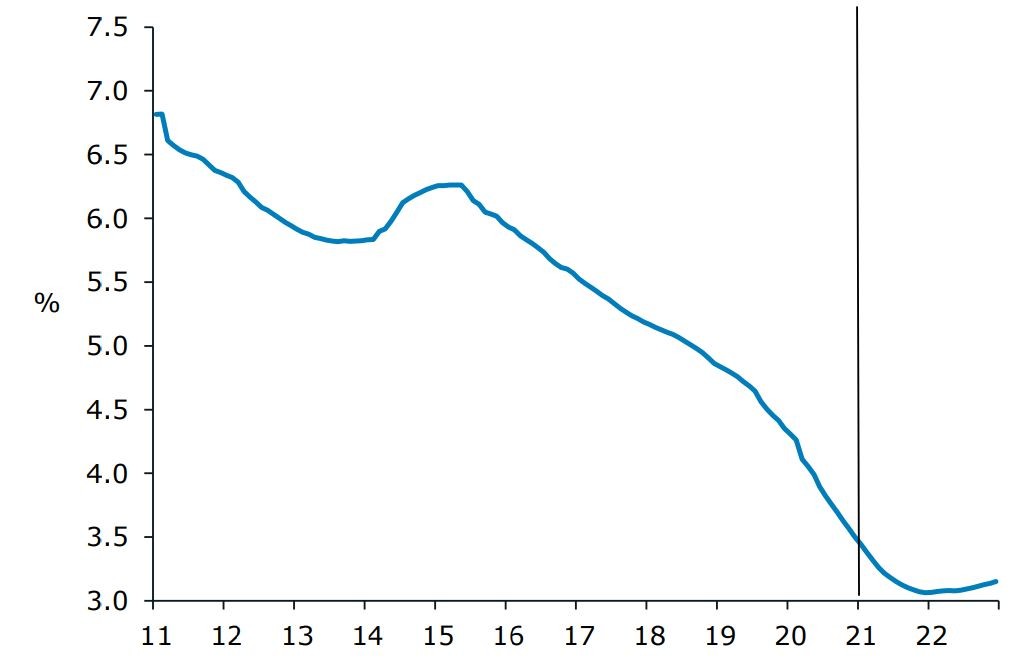

We estimate the “effective mortgage rate”, which we define as the average mortgage rate faced by borrowers in aggregate, by observing past fixing behaviour and the rates prevailing at the time, then projecting this forward based on a number of assumptions.

While discounts, early repayments and switching complicate the picture, we can estimate the effective rate reasonably accurately, and our analysis shows that it is likely to continue to fall this year (figure 5) even if mortgage rates don’t fall any further, or even start rising a little.

That is mostly because any borrower rolling off a historic fixed rate (or a floating rate) into a new fixed rate today will pay a lower rate. Eventually, the effective mortgage rate will rise, but with a lag.

Our projections assume that higher longer-term wholesale interest rates will eventually put upward pressure on longer-term fixed mortgage rates. However, they also recognise that many borrowers will simply select the lowest rate on offer.

This will affect the composition of borrowing and provide something of an offset.

But how these forces offset each other is impossible to say.

As such, our projected effective mortgage rate should be treated as an assumption, not a forecast, as we cannot accurately predict borrower behaviour.

We assume that the OCR remains on hold over the projection period, but once the OCR is lifted, the effective mortgage rate will increase further than what is shown here.

Figure 5. Effective mortgage rate

Source: RBNZ, ANZ Research

The increase in debt that has accompanied the recent strength in the housing market will determine how much rising interest rates will impact disposable incomes faced by households.

Increased indebtedness makes households more vulnerable to changes in their financial positions – including income changes and higher interest rates.

Given this sensitivity, high debt levels are a constraint on how far interest rates can move higher, and how fast.

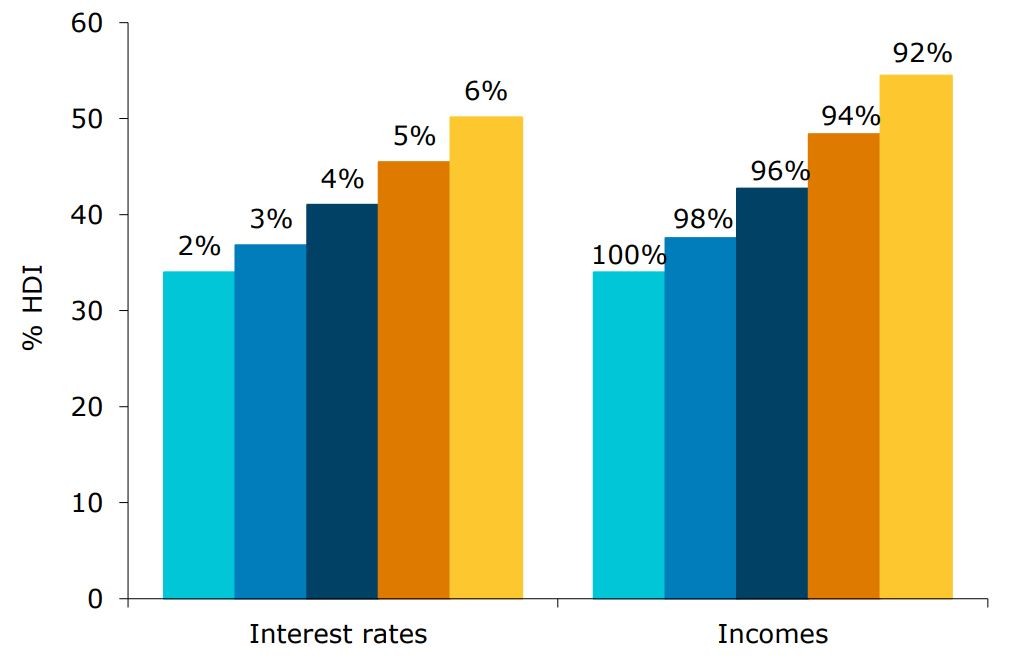

Given that we expect moves in interest rates will be very gradual, we do not expect that higher interest rates will be a financial pressure point in aggregate, but debt-servicing will naturally become more expensive and some households may find this difficult, particularly if they have entered the housing market only recently with very high levels of debt (figure 6).

Figure 6. Sensitivity of debt-servicing costs (as a share of aggregate incomes) to changes in interest rates and aggregate incomes for a new mortgage borrower

Source: REINZ, Statistics NZ, RBNZ, ANZ Research - Note: This is based on a new borrower buying the median house, with a 20% deposit and average household income.

Of course, if the economy is overheating and inflation takes off, then the RBNZ may need to respond more aggressively than incorporated in our current forecasts.

And there is always a risk that dysfunction in wholesale funding markets could see interest rates spike even more than this, but we expect the RBNZ would move swiftly to lower the OCR (potentially taking it negative) in that case.

The greater risk, given recent debt accumulation, is the possibility that pressure points emerge in response to unexpected income strains.

Overall, we expect that debt servicing will remain easy for a long time, given structural shifts towards lower interest rates and the expectation that increases will be gradual from here.

But households do need to prepare for the possibility that a greater proportion of their incomes may need to be directed towards mortgage costs in time. Bank liquidity has been abundant

Another key contributor to the recent boom in the housing market has been abundant bank liquidity, particularly strong deposit growth.

This has ensured that plenty of funding has been available to respond to strong credit demand, which has seen new mortgage lending increase rapidly as housing turnover has surged (figure 7).

Figure 7. Housing turnover and new mortgage lending

Source: RBNZ, REINZ

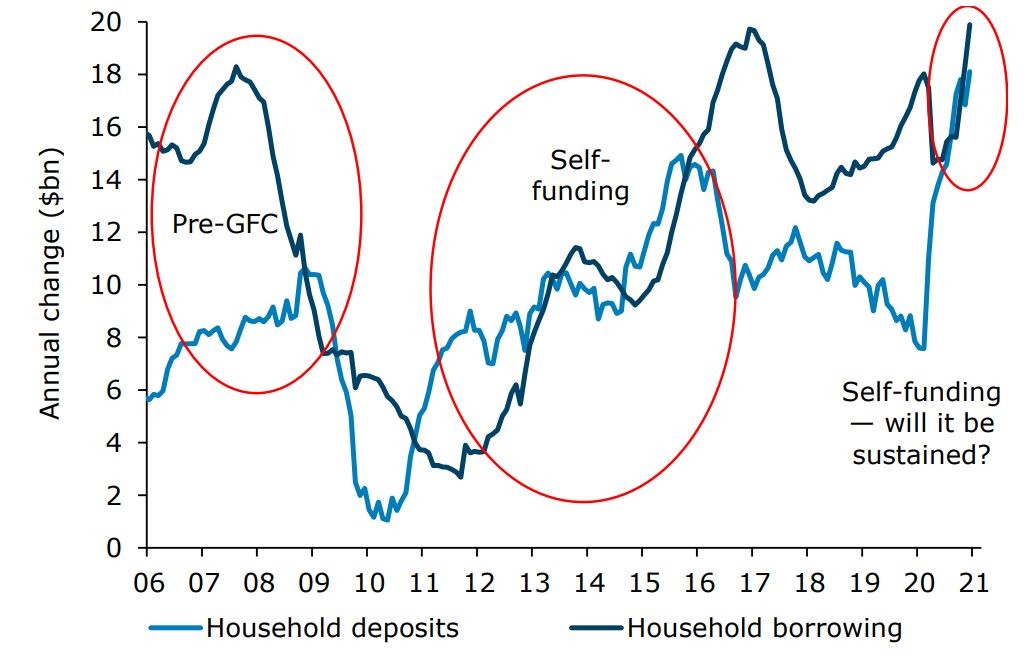

Strong deposit growth has allowed banks to largely “self-fund” – that is, growth in mortgage lending has been almost fully met by new growth in household deposits (figure 8).

Banks have not needed to tap other funding sources, with plenty of funding readily available to meet the surge seen in credit demand.

Figure 8. Bank “funding gap”

Source: RBNZ, ANZ Research

Strong deposit growth has been driven in large part by the RBNZ’s LSAP programme, which in combination with the wage subsidy injected billions of dollars into the bank accounts of households very quickly.

Although bond purchases under the LSAP scheme are directed to markets, purchases do filter through into increasing deposits in the banking system.

It is this phenomenon, rather than a change in saving behaviour or the like, that has driven the recent run-up in deposits.

This strong deposit growth from the LSAP has also put downward pressure on deposit rates, which itself has helped keep mortgage rates low.

Because this extra cash in the system is mostly sitting in call accounts or relatively short-duration term deposits (a cost of funding for banks not too different from the OCR), banks have not really needed to draw on the FLP for funding, with around $1.6bn drawn from the scheme by mid-March.

Credit supply is expected to be more limited going forward

Although deposit growth will remain supported by the continuation of the LSAP, the impetus to deposit growth will wane as the LSAP is pared back and fiscal stimulus dissipates.

This will naturally reduce the extent to which banks can self-fund. This, in turn, will tend to cool mortgage lending, with banks faced with the decision to either ration lending or raise funds through other means, which would exert upward pressure on mortgage rates.

Depending on how much funding is required, banks might be able to plug the gap with wholesale funding (ie issuing bonds).

This is generally a more expensive source of funding than domestic deposits, but because wholesale funding is a not the dominant source of funding and yields have come down a fair amount, the impact on mortgage rates would likely be relatively small.

Alternatively, if the gap between credit demand and deposit growth becomes very large, banks may need to start competing harder for domestic deposits, and there’s only one way they can do that – higher deposit rates.

That’s a higher funding cost that could lead to higher lending rates.

There’s not much sign of it yet, but it’s a very plausible development.

Savers will be crossing their fingers. Banks can also draw on the FLP, and we do expect take up of the scheme to increase in time. The RBNZ has committed to keeping the scheme in place till mid-2022.

Given that banks know that they have plenty of time to access the scheme, they will likely do so when it better suits gaps in their funding profiles, rather than immediately.

As deposit growth slows, this will also gradually lift the incentive for banks to draw on the FLP.

The FLP is expected to help to bridge some of the gap that may emerge between credit demand and supply as deposit growth slows, and may mean banks do not have to raise deposit rates as soon or by as much.

But the scheme will only account for a small portion of banks’ total funding and banks will want to carefully manage the risk of being too reliant on the scheme at particular time horizons, since they will need to replace the funds with other sources down the track.

This means that any offset to bridge any funding gap or alleviate upward pressure on interest rates is only likely to be partial.

All up, this means that under the scenario where credit demand remains very strong for an extended period, but deposit growth slows, credit conditions are likely to “naturally” tighten.

Credit conditions to weigh, including policy changes

At the same time as bank liquidity is expected to become less abundant, we may see banks become more cautious about riskier lending, given the sheer rise that has been seen in house prices and the apparent unsustainability of current market conditions, particularly if funding is more of a constraint.

We have already seen this start to play out with banks moving pre-emptively to tighten investor loanto-ratio caps ahead of their re-imposition by the RBNZ.

The RBNZ re-imposed previous restrictions effective from March 1, after removing them temporarily at the onset of COVID-19.

They are also proposing tightening restrictions on investors from May 1 (limiting lending with equity of less than 40%).

These changes are helpful in limiting the build-up of financial stability risks and may curb house price inflation to some degree, but they are not expected to have a large persistent impact on the market (similar to when restrictions have been tightened previously), particularly because equity positions have increased so much on the back of recent house price gains.

Figure 9. House sales and prices

Source: REINZ, ANZ Research

That said, the restrictions could act as to curb some momentum in the market, contributing to a deceleration that we expect is coming as affordability considerations and broader credit headwinds start to weigh.

Consistent with this, the RBNZ expects the changes may rein in some “irrational exuberance” in the market.

But given recent the sharp run-up in the market that we have already seen, it may be too little too late to curb expectations that could prove to be unfounded.

Other policy changes could also weigh on housing demand, with the Government expected to make announcements next week.

It is uncertain what changes might be considered, but they could impact credit conditions. For example, advice has been sought on a possible cap on interest-only investor loans.

This would directly affect credit availability to certain investors but it is unclear how many potential buyers would be affected.

Nonetheless, it could reduce demand at the margin, with potentially significant impacts on the cash flow of some investors, especially if they are highly leveraged.

Debt-to income limits are also another possibility, but the hurdle to implementing these is higher.

Nothing lasts forever

Easy financing conditions have contributed to the recent spectacular run in the housing market, but while stimulatory financial conditions will be in place for a while yet, support provided to the housing market through these channels is expected to diminish.

Barring an unforeseen negative event, interest rates are expected to increase gradually from current record lows, with debt-servicing costs moving slowly higher as higher mortgage rates pass through to costs faced by households.

At the same time, abundant bank funding will be whittled away as deposit growth naturally slows, and banks are also expected to be prudent in their lending decisions, with recent policy changes contributing.

An eventual tightening in financing conditions is expected to weigh on the housing market in time, alongside affordability constraints and other headwinds.

However, recent strength in the housing market appears to have been fuelled, in part, by expectations that current easy conditions will continue, interest rates will stay very low indefinitely, and that further capital gains are a sure thing.

This means that some people’s expectations may be disappointed, potentially leading to a more marked cooling in the market when headwinds do start to weigh.

The fact is: nothing lasts forever.

Current financing conditions reflect a unique set of circumstances that are now evolving. The pace of recent house price gains cannot continue in perpetuity. Participants in the housing market should be mindful of this fact.

RELATED ARTICLES

NZ Business

Sweet Deal – NZ-EU FTA a win for primary producers

NZ Insights