NZ Insights

Bubbling with excitement - Making Sense of the Trans-Tasman Bubble

Sharon Zollner, Chief Economist, ANZ NZ

Finn Robinson, Economist , ANZ NZ

Summary

The tourism sector has been doing it extremely tough in the past year, and got some welcome good news this week in the fact that travel between Australia and New Zealand will be quarantine-free from 19 April.

This announcement is great news for people who can now reconnect with friends and family across the ditch, and for businesses who rely on international tourism.

But what matters for policy makers and the macroeconomic outlook is the impact of the travel bubble on economic activity, and this is very hard to quantify.

➤ In the year to December 2019, personal travel between New Zealand and Australia added just over NZD500million to the domestic economy on a net basis – around 0.2% of annual nominal GDP at the time.

➤ However, history will not be a reliable guide. The world has changed since the border was last open to Australians, and while there are strong incentives to come to New Zealand (where else is there to go?), there are also strong deterrents (“flyer beware”). It’s difficult to be definitive about the economic impact in light of these uncertainties.

➤ The sheer difference in populations means that the overall GDP impetus from the trans-Tasman bubble is likely to be positive, but overall, we suspect the net contribution to growth from trans-Tasman travel might not be as large as pre-COVID numbers would imply, at least initially.

➤ Even if Australian demand for New Zealand tourism services is high, there’s a risk that the tourism industry may not be able to find enough staff to bring the industry back up to capacity.

➤ Timely data like daily border crossings will give us some indication of the level of take-up of trans-Tasman travel, from both the New Zealand and Australian sides.

The historical evidence

It’s really hard to know right now what impact the travel bubble will have on New Zealand’s GDP.

That’s not least because the world has changed a lot since trans-Tasman travel was last possible, and history will therefore not be a reliable guide going forward.

However, looking at the historical contribution of personal trans-Tasman travel gives us a sense of how important this channel has previously been.

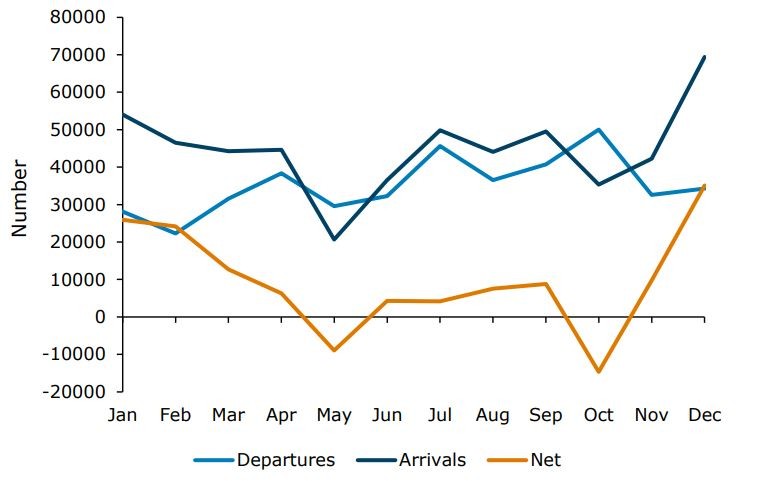

One point to note is that there are times of the year when trans-Tasman travel has tended to be a net drag on New Zealand’s GDP.

Figure 1 shows the usual seasonal pattern of holiday travel (versus those visiting friends and family, or business travellers) between Australian and New Zealand. (With departure cards gone, we only have data up to 2017.)

We come out only slightly ahead in the winter period, and some months even see more departures than arrivals. But on average, many more Australians come to New Zealand than vice versa over the year.

This indicates that while there’s a decent chance that while the GDP implications of the travel bubble for New Zealand over winter could be pretty minimal, overall it should be positive for the year.

Figure 1. Typical seasonality of trans-Tasman travel (average 2014-17)

Source: Stats NZ, ANZ Research

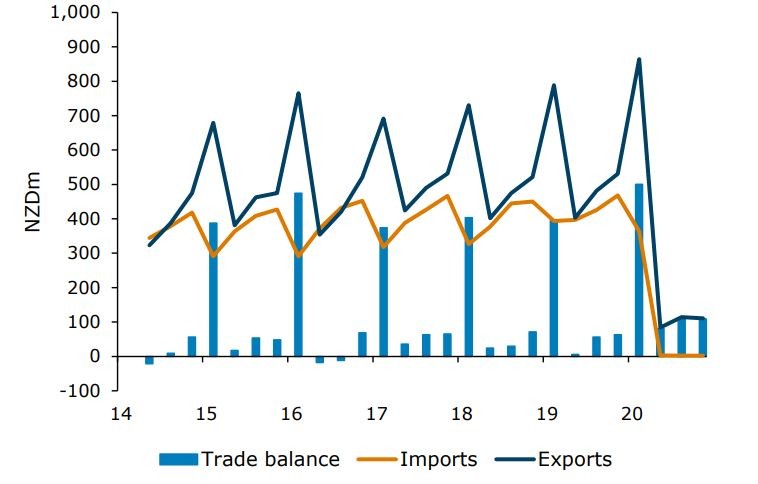

For a fuller picture, we can also look at the balance of payments data, which captures not only visitor numbers, but also their spend.

Figure 2 shows the pre-COVID value of Australian visitors to New Zealand (personal travel services exports to Australia), versus the expense of our personal travel to Australia (personal travel services imports from Australia).

The balance is then how much, on net, personal travel between Australia and New Zealand adds to the economy.

Overall, trans-Tasman personal travel is indeed typically a net win for New Zealand in GDP terms. In 2019 personal travel between Australia and New Zealand added over $500m to the economy – around 0.2% of nominal GDP over the year.

One note of caution here is that quite different estimates of the personal travel trade balance were obtained when using equivalent data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This data showed an AUD1.3bn personal travel services deficit for Australia in the 2018/19 financial year (surplus for NZ), which is roughly NZD1.4bn. The story is qualitatively similar, however – we usually operate a personal travel surplus with Australia, and this is likely to continue as the travel bubble opens. And, given the uncertainty about the impact of the travel bubble, it’s probably not a good idea to be too attached to a single number anyway.

The vast bulk of it typically comes during the peak summer period. In 2020 Q1 alone, just before borders shut, trans-Tasman personal travel added a net $500m to the NZ economy – that’s nearly the same as the whole of 2019.

Figure 2. Value of personal travel with Australia

Source: Stats NZ, ANZ Research

This time really is different

History is one thing, but times are clearly far from normal. One obvious deterrent to travel is that people could get stuck on the wrong side of the ditch, which could be extremely costly.

It’s impossible to know in advance how willing people will be to take this risk. Another consideration is that there will be a lot of Australians rushing over to visit family and friends in New Zealand that they have not seen in a year.

Even in the years before COVID, such visitors consistently made up a bit over 40% of Australians coming. They are less likely to splash out on expensive tourist activities or hotels, and thereby will make a smaller contribution to GDP during their stay.

And they are likely to make up the majority of early arrivals, being the most impatient to get here. Of course, providing an offset in GDP terms, similar characteristics are likely to be true of Kiwis heading to Australia.

Departure-card data shows that historically the mix of visitors is very similar, and it’s just as likely that the first rush of Kiwis heading to Australia will be those reconnecting with loved ones, rather than those splashing out on Gold Coast holidays.

There’s one other important point to bear in mind – the Australians have nowhere else to go.

There are 25 million of them who haven’t been able to travel internationally for a year, and right now the only option is New Zealand.

In recent years, New Zealand saw around 1.3 million Australian visitors each year, versus around 11 million outbound international trips by Australian residents in 2019.

What proportion of would-be travellers will impatiently head to New Zealand versus those who prefer to wait for their world to get bigger is impossible to predict, but will have a huge say in how things turn out.

If even 20% of the usual number of overseas trips by Australian citizens were directed to New Zealand, that would be 2 million people visiting our shores.

New Zealand couldn’t possibly match that, given the relative sizes of the two populations. Yet another source of uncertainty is whether the New Zealand tourism industry could sustain a large influx of overseas visitors.

Businesses need staff to operate, and many businesses in the tourism industry hire staff from overseas.

With this pool of labour still largely cut off, there’s a question of whether there will be enough workers to be able to bring the tourism industry back to full capacity, even if the demand is there.

And finally, it seems unlikely to remain a two-country bubble for long. Once Pacific Islands are included, we’ll have more choice of places to go – and so will the Australians.

And unlike trans-Tasman travel, those flows will be heavily lopsided (ie boosting services imports).

"Just as retail was boosted by people running down their abruptly purposeless holiday savings, that will now switch to a headwind, as people rebuild those savings, dreaming about their next international getaway."

Winners and losers

The introduction of the trans-Tasman bubble will clearly benefit the international tourism industry, which has suffered greatly from the pandemic. It’s a game-changer for Queenstown. But there will be losers too.

The option of traveling to Australia will reduce domestic tourism, which areas like the Coromandel, Northland and Napier will notice.

And businesses may notice reduced spending on other nice-to-haves (spas, e-bikes, fancy dinners) that have been substituted for international holidays over the past year.

More generally, just as retail was boosted by people running down their abruptly purposeless holiday savings, that will now switch to a headwind, as people rebuild those savings, dreaming about their next international getaway.

How can we track the impact of the bubble?

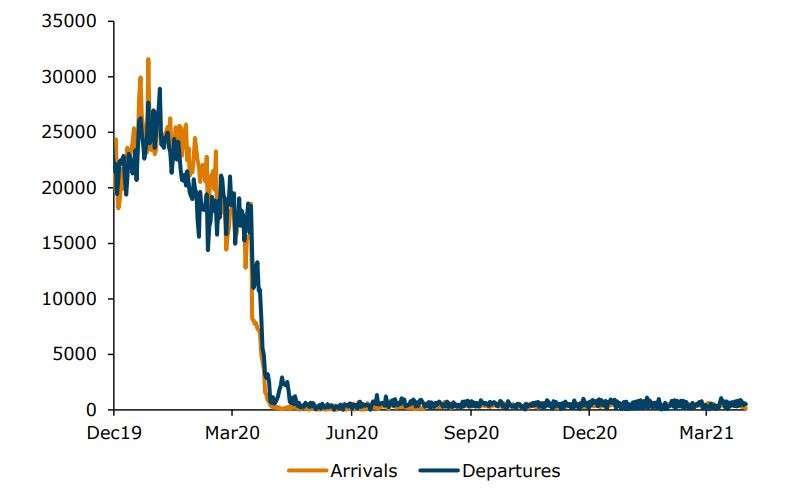

There are a few key places we can look to in order to monitor the impacts of the travel bubble. The first is daily border crossing data from Customs NZ.

These crossings have been close to zero since the border first closed in March, restricted by the capacity of MIQ (figure 3). Any significant change in arrivals and/or departures should reflect trans-Tasman travel.

Figure 3. Daily border crossings

Source: Stats NZ, NZ Customs

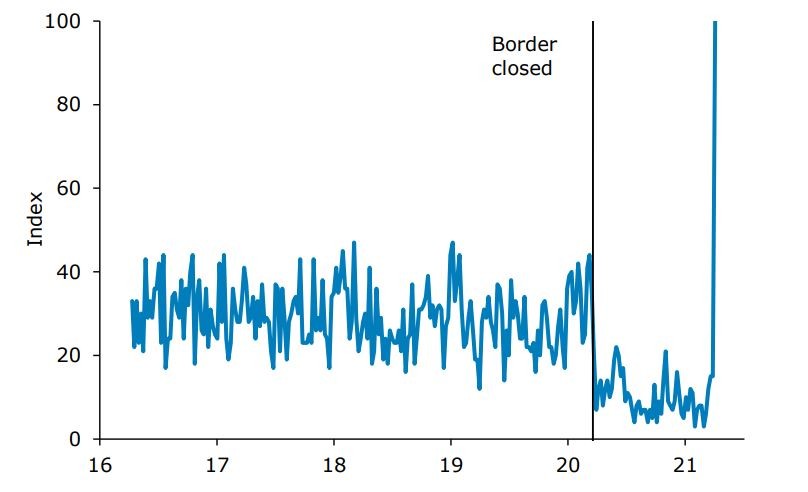

Google Trends data can also be used to gauge interest in trans-Tasman travel.

While googling flights to Australia is by no means a guarantee that you’ll buy a ticket, the data are timely and should give some sense of how enthusiastic people are to travel.

Already we’ve seen a sharp uptick in interest in travel to New Zealand by Australians (figure 4).

Figure 4: Australia Google searches for travel to New Zealand

Source: Google, ANZ Research

And while Balance of Payments data is only available with a long lag, we’ll keep an eye on spending on Australian credit cards in New Zealand. One final point.

While the impacts on GDP might not be a game-changer, a trans-Tasman bubble will undoubtedly save many firms who are on the edge, direct resources towards parts of the economy that have more spare capacity, reunite families, and do wonders for relieving our collective sense of claustrophobia.

GDP is a woefully inadequate measure of wellbeing and there’s so much more to it than that. This marks an important milestone on the long road back to a more normal way of being. Bring it on.

RELATED ARTICLES

NZ Business

Sweet Deal – NZ-EU FTA a win for primary producers

NZ Insights